In a time period when less than a year ago 20-year-old Michelle Carter was sentenced to 15 months in prison for a series of encouraging text messages to her boyfriend, Conrad Roy III, that led to his eventual suicide, Director Matt Walting’s funereal “Just Say Goodbye” is not only a call to arms for suicide prevention, but, more importantly, awareness.

The movie, filmed on a scant budget of $13K, imbues its message slowly, carefully, and without apology. This is an important film, that works not by its acting, but its tone and lasting effect. Suicide in movies is often preceded by motive – as penance for wrongs perpetrated by the offender, or a way to escape inescapable crimes. But we seldom see a focused and unforgiving picture that paints suicide as the disease it is, a disease that affects not just its victims, but those it leaves in its wake.

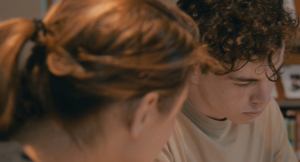

“Just Say Goodbye” is sold to us not by its intended victim Jesse (a subdued actor named Max MacKenzie), but his best friend, Sarah, played by Katerina Eichenberger with a skill so sharp it defies her slim filmography that includes only this, a TV mini series, and an independent short. She learns early in the film that her best friend Jesse intends to take his own life on his birthday, weeks away, coinciding with a trip she has planned to New York City with her father. She takes the news poorly, spending the rest of the film trying to change his mind with everything she knows – reason, emotional entreaty, pleading…but he seems set in his course.

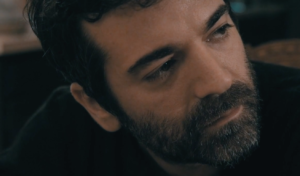

The adults in this film are absent – physically, emotionally, or both. Jesse’s father (William Galatis) is an unemployed and verbally abusive drunk whose wife killed herself when Jesse was 6-years-old. He doesn’t bring this up in healthy ways unless pressed, remarking at one point he drinks because Jesse’s presence reminds him of his wife’s passing. There’s an additional subplot on this, involving a wealthy neighbor and her son Chase that is a constant bully to Jesse, but it’s rather distracting, and to say more would take away from the film as a whole, so I will not comment on it further.

The acting is hit or miss. Eichenberger steals the show, acting circles around Jesse, his father, the aforementioned Chase (Jesse Walters), and most everyone else in equal measure. Sarah is radiant, gorgeous, inspirational, and caring – representing an existence and beauty Jesse could have if he chooses life. In a perfect piece of filmmaking, this beauty exists not as something as clichéd as romance, but something as sublime as the kind of love and acceptance only true friends can offer.

Eichenberger imbues this with ease – she’s easily the best actor in any indie I’ve seen in the last year or more. This is no more evident than in the film’s greatest piece of cinematography, as a terrified Sarah, hanging on to fleeting hope, repairs a calendar she has ripped in half – hanging it between one poster that says, “life is a beautiful ride,” and another that reads, “perseverance” – in one of the smartest shots I’ve seen in an indie, ever.

As Jesse, MacKenzie’s acting is sardonic and irreverent for most of the film – until he’s forced to confront his feelings for Sarah and, in equal measure, life without her when she will eventually leave him for college, in a scene that is utterly heartbreaking. Walting and writer Layla O’Shea couple this with sympathy for Jesse’s character, which is written as an irrational path of self destruction. Jesse often makes you angry at him, while also causing sorrow for the circumstance he’s found himself in. This is especially true toward the film’s conclusion as he tries all the wrong things to get better while avoiding the one thing he should truly do.

Ancillary characters such as Chase are painted thinly and serve mostly to show the desperation Sarah finds herself in (even as the film paints Chase in a quasi-sympathetic light as we see his absentee and entitled mother contributing to his upbringing in catastrophic ways). While Jesse means to kill himself, it’s Sarah’s struggle we feel the most starkly. We feel for Sarah; not only for her pain as she watches her friend suffer, but for the torture she endures struggling to accept the mantle of responsibility that accompanies the news privy only to her.

Ancillary characters such as Chase are painted thinly and serve mostly to show the desperation Sarah finds herself in (even as the film paints Chase in a quasi-sympathetic light as we see his absentee and entitled mother contributing to his upbringing in catastrophic ways). While Jesse means to kill himself, it’s Sarah’s struggle we feel the most starkly. We feel for Sarah; not only for her pain as she watches her friend suffer, but for the torture she endures struggling to accept the mantle of responsibility that accompanies the news privy only to her.

“Just Say Goodbye” smartly makes sober commentary on the mental health system, as we discover, through the reading of a heartbreaking letter left to Jesse’s father by his late wife, that she was not “crazy” as his father so often minimizes, but suffering from undiagnosed postpartum depression the film’s characters were ill-equipped to realize.

“Just Say Goodbye” makes you anxious, uneasy, afraid. This is its greatest asset and smartest filmmaking choice. A movie like this, that wishes to impart the feelings it does, would do its audience a disservice by making its viewers feel something as common as sadness. It’s something much deeper and tragic we’re watching unfold here.

I will not divulge what happens to Jesse. It would be a degradation to this film, which is about the mechanisms and hopelessness of depression – a hopelessness that affects not only its victim, but those closest to him. We’re meant to feel Jesse’s depression, but, in greater measure, Sarah’s pain and fear. The film accomplishes this remarkably and without error.

At the end of the day this is just a remarkable film. At 1 hour and 46 minutes it never drags. It suffers from some acting missteps and script issues, but its larger impact more than makes up for it. “Just Say Goodbye” is still rounding the festival circuit; but if you get the opportunity, do yourself a favor and see this poignant and heartbreaking work.

– by Mark Ziobro