The stories of Samurai, or Japanese warriors, have captivated people’s interest for decades. Their exploits, legends, and history have been chronicled in countless Japanese films such as “Samurai Rebellion,” “The Twilight Samurai,” and “Seven Samurai.” The captivation has even passed to American cinema such as the historical “The Last Samurai” (2003), and even in more entertaining films such as the “Kill Bill” saga. Their code, their honor, and their dedication in battle enthralls us. However, less attention is often paid to hardships faced by “ronin,” or masterless Samurai during times of peace.

“Harakiri” (Seppukku, original title) (1962) is an excellent Japanese Samurai film dealing with this topic. The film, by Director Masaki Kobayashi, is an insightful, reminiscent, and expositional masterpiece; it tells the story of two fateful ronin, and a family threatened by dire circumstance but held together by an unbreakable loyalty.

Of Critiques of Codes of Honor and Desperate Times

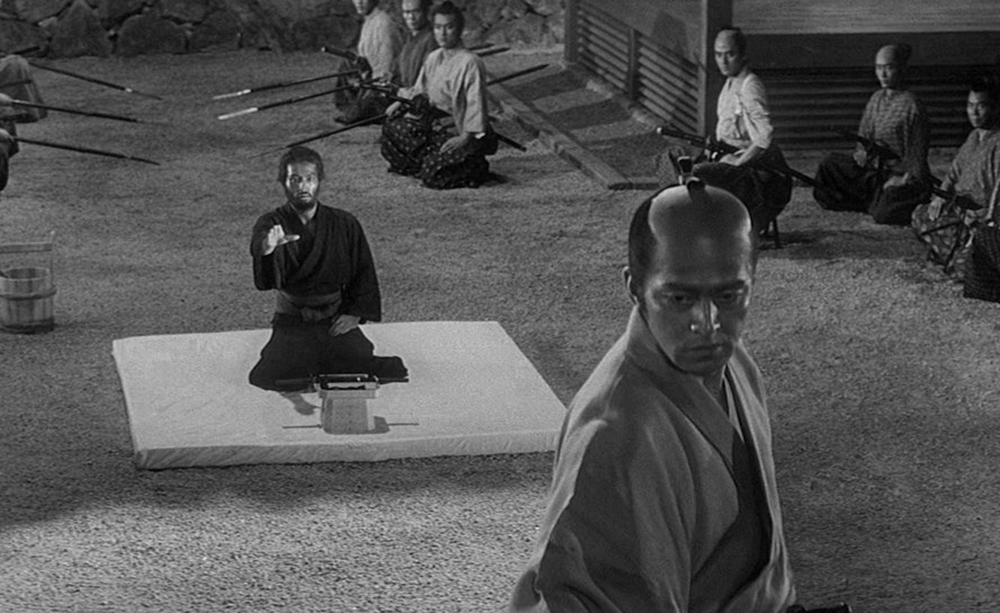

The film begins with Hanshiro Tsugumo (Tatsuya Nakadai), a seemingly starving and desperate Ronin, showing up at the gates of the Iyi clan with the intention of using their forecourt to commit harakiri (a ceremonial honor-suicide characterized by self-dismemberment followed by beheading). While such honorable suicide was once popular for fallen or disgraced samurai, the practice has been skewed as of late by a wave a samurai who show up at many clan’s dwellings, using Harakiri as a means to elicit money or job positions from clans. The lyi clan has grown tired of the practice, and are particularly weary of Tsugumo when he arrives.

One of the lyi clan recants the reason to Hanshiro—another samurai, named Motome Chijiwa, had recently come to their property requesting their forecourt for the same reason—however, there had been disastrous results. Chijiwa had initially been granted an audience with the clan’s lord; however, upon learning that the lord was not present, and that he must, in fact, commit harakiri, Chijiwa angles for a couple days leave to tie up loose ends before ending his life. However, the lyi clan, thinking he is a fraudster and means to dishonor their name, forces his hand. He is forced to commit harakiri and worse—an examination of his samurai sword (said to be the samurai’s soul) reveals it is made out of bamboo. However, the angry clan doesn’t lend him a real sword, insisting that his own blades would be the most honorable end.

Cinematography that Captures the Story’s Essence

The scene that follows is as difficult to endure for the audience as you can imagine the actual scene would be for Motome. The filmography is very well done, lingering on a scene when a movie would usually cut, and using steady camera shots and unique angles to paint the bitter end of the frightened samurai. That Motome was not using harakiri as a ruse to barter for charity is a point the audience soon learns.

The following exposition and chronology that Hanshiro uses to tell the story of his deceased friend to the lyi clan as he awaits harakiri unravels slowly, yet captivates us completely.

With detail, we learn that Motome’s father had taken his life via harakiri at the fall of his master’s castle, leaving Motome in Hanshiro’s care. Hanshiro does his best, raising both Motome and his own daughter, Miho (Akira Ishihama). However, the relationship between the three becomes more complicated when Hanshiro must convince Motome to marry his daughter at the onset of severe financial problems and an unwillingness to hand her over to subservience to a distant lord.

As his tale continues, we learn of the worsening condition of the small family. Both fallen samurai unable to find work—and a baby added to the mix—causes both Miho and the infant to fall ill, and Hanshiro and Motome desperate to find a solution. However, no solution presents itself, and Motome, unable to borrow money even from an unscrupulous lender, travels to the lyi clan’s court—in hope of some financial incentive to provide for his family—which ends in his dishonorable end when the lyi clan force him to commit harakiri.

A Different Kind of Revenge Film

Make no mistake about it, “Harakiri” is a revenge film. However, where it shines above others of its type is in the filmography, in the story, and in the attention to detail. Unlike “Kill Bill,” it lacks much action and fight sequences, and lies in its storytelling and character development to make you care for Motome and Hanshiro. In the beginning you have little insight into Motome’s actions (such as why he carries bamboo swords, considered a disgrace for any samurai). By the end you won’t find his actions disgraceful but logical and honorable. And you will realize, much like the lugubrious lyi clan, that more care into understanding his backstory could have averted the whole, tragic chain of events from unfolding.

Part of the “Criterion Collection,” there’s a good chance, if you are only an avid viewer of American movies, that you might have missed this gem. But if you have the opportunity, you should make an attempt to see it. “Harakiri” starts slow, but once you are in the world of these two men, you quickly find yourself transported back to Tokugawa Japan and eager to stay there. The story is developed and mesmerizing. And while we won’t spoil the ending here, it is worth waiting for. While lacking in the usual action-packed excitement you may be used to, it offers a conclusion befitting to the lives of Motome and Hanshiro—and befitting to a loyalty between two men running much deeper than a code of honor.