Despite a few popular outliers (like 1999’s “The Blair Witch Project”), the ‘found footage’ genre has only been embraced by studios and moviegoers relatively recently. Successes include monster flick “Cloverfield” (2008) and the voyeuristic “Paranormal Activity” series (soon to release its fourth installment). But while many of these hits have been horror films, we’ve seen the techniques of hand-held, shaky-cam cinematography expand elsewhere, particularly into action films (Paul Greengrass’ entries in the “Bourne” espionage series, for example).

While such hand-held camerawork can lend a great deal of intimacy and verisimilitude to a film, it has been grossly (and, for some viewers, nauseatingly) overused in many instances. So how does hand-held buddy-cop drama “End of Watch” fare? While the film does offer some solid acting a rare commitment to character development, its dizzying cinematography and inconsistent internal logic are too flawed to overlook.

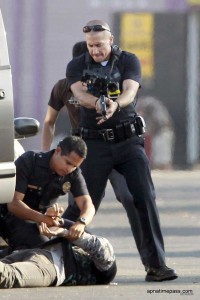

Writer/director David Ayer has made a modest career penning cop-centric thrillers, ranging from brain-dead (2003’s “S.W.A.T.”) to highly-engrossing (2001’s “Training Day,” for which Denzel Washington won a well-deserved Academy Award). “End of Watch” falls somewhere in between. The film gives us a sort of slice-of-life look at the careers of two LAPD patrol officers, partners Taylor (Jake Gyllenhaal) and Zavala (Michael Peña). Taylor is taking a film class on the side, which ostensibly explains why he is filming everything with a portable camcorder. We see the patrolmen responding to calls, filling out paperwork, and bantering with their fellow officers, all intercut with scenes of the two of them chatting about personal things like vacations and their significant others.

The overarching plot reveals itself gradually. A chance traffic stop for an obstructed rear-view mirror leads to an arrest involving hidden cash and designer firearms. Following up on this case leads them to a cartel-run human trafficking operation and a major drug bust, culminating in the cartel’s Mexican leadership sending out a heavily-armed hit squad. Taylor and Zavala are led into a trap and pinned down by gunfire, forcing them to shoot their way out in a dramatic and bloody finish.

Gyllenhaal and Peña turn in a pair of fine performances as the leads, and they are aided by plenty of space for conversation. Their close relationship is built on plenty of banal smalltalk, a handful of tense situations in the line of duty, and some drunken pronouncements of affection and brotherhood at Taylor’s wedding. While neither character is particularly bright, and they share a casual disregard for procedure and legality in their work, they are presented in an unvarnished, credible way that makes them very real. Unfortunately, the film’s missteps undermine this lone compelling feature.

The cinematography is, quite simply, a mess; viewers prone to motion sickness will find it agonizing to watch. We get so many sequences that are choppily-edited, poorly-framed, and woefully unfocused that it is difficult to maintain interest in the action, even if you can bear watching it. While it’s certainly reasonable that someone might not be capable of the best camerawork while in the midst of a shootout, the entire premise begins to falter when it is examined more closely.

Within the first few minutes, we get shots of both Taylor and Zavala (who carry miniature lapel-cameras) in frame together, along with what is supposed to be Taylor’s lone hand-held camera. So who is shooting that? Trying to undermine the fundamental conceit of filmic suspension of disbelief – that is, willfully setting aside the knowledge that someone filmed the action, thus making it artificial – seems utterly pointless when it is discarded so abruptly. Further, we get multiple scenes of the gun-toting cartel foursome, who also dabble in amateur cinematography (and who are inexplicably fine with recording each other’s identities and misdeeds, while being sure to mask their faces during the shootings), but we also get some aerial establishing shots of LA in the mix. It just doesn’t add up, and that makes the whole exercise seem pointless.

Within the first few minutes, we get shots of both Taylor and Zavala (who carry miniature lapel-cameras) in frame together, along with what is supposed to be Taylor’s lone hand-held camera. So who is shooting that? Trying to undermine the fundamental conceit of filmic suspension of disbelief – that is, willfully setting aside the knowledge that someone filmed the action, thus making it artificial – seems utterly pointless when it is discarded so abruptly. Further, we get multiple scenes of the gun-toting cartel foursome, who also dabble in amateur cinematography (and who are inexplicably fine with recording each other’s identities and misdeeds, while being sure to mask their faces during the shootings), but we also get some aerial establishing shots of LA in the mix. It just doesn’t add up, and that makes the whole exercise seem pointless.

“End of Watch” has a few moments of high drama, but these are typically very grisly, featuring lots of disturbing imagery and near-constant profanity; it is not for the faint of heart. Ultimately, it’s a shame that two fine performances have been marooned amid such an ugly, unpleasant morass.

– by Demian Morrisroe