Spanning four years, from 2013-2017, Irish filmmaker Bertie Brosnan created a series of independent short films that he considers ‘artistic.’ “My short films are mostly arthouse, mystery, and possibly dark,” Brosnan stated to me when I gathered the films to watch. And that they are. The films, “Jacob Wrestling with the Angel,” “Sineater,” “Forgotten Paradise,” and “Last Service” deal with heavy themes; and are linked by common bonds of introspection and symbolism.

Shorts are a difficult genre to master. There’s no such thing as too short or too long – but the length has to be right for the material. With his longest short, “Jacob Wrestling with the Angel” capping at 14 minutes, Brosnan has, for the majority of these works, picked the right length. With a dearth of dialogue, and an abundance of imagery, symbolism, and allusion, Brosnan has created a series of films that will please lovers of independent films; though they may be harder to access for those looking for a straightforward narrative.

Lovers of Hollywood films such as “Vanilla Sky” or “Only God Forgives” may get the most out of Brosnan’s shorts, as they are ethereal and dreamlike, and seldom straightforward narrative. The films have strong narration and expositional tools to carry us along, even if the material is dense and, for lack of a better word, big.

His most dreamlike, “Jacob Wrestling with the Angel,” is filled with imagery and waxes and wanes out of reality. It’s a tad too long, and rambles some, but it’s Brosnan’s first professional short film and some experimentation is expected. He paints his main character (played by Brosnan) as both protagonist and victim in equal measure. He appears inquisitive yet perplexed, caught in the confines of misery and depression. He pops pills to deal with “reality.” He is a product of a modern generation who doesn’t know who or what to be – or even what is real.

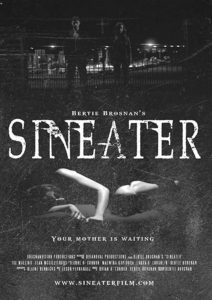

The symbolism in this film, as with his other shorts, is strong. For instance, in “Sineater,” a movie about a man named Jack (Seán McGillicuddy) who is forced to look upon his past wrongdoings, symbolism is used to detail what of Jack’s actions are ‘sins’ and what are simple regrets. In one of the film’s best shots, the Sineater, a mysterious man named ‘The Driver’ (Joe Mullins), drinks what appears to be a shot of liquor while Jack makes a tragic mistake which ends up in a friend’s death. Is it liquor, though, or Jack’s sins the mysterious driver imbibes? It’s left up to the imagination. Jack is also, towards the film’s close, left at a literal fork in the road after facing his demons the night before. While the shot is obvious, as perhaps is even Jack’s path, it’s an important shot nonetheless.

We have equal symbolism in “Jacob Wrestling with the Angel,” as the film’s protagonist, for much of the film, is literally struggling to complete a painting at a canvas. Paintings are subjective – to the viewer. But to the artist they represent something else – reality as seen through their eyes. And while the adage in narration – that it is better to show than to tell – is true, Brosnan breaks this rule with favorable results. Parts of this film narrated by Hughes (whom I believe to be the Angel, although others may have a different interpretation), and cut with images of scenes we’ve already seen, explains to us what we saw – which isn’t a detriment. Brosnan is not only clarifying some of the film’s more ambiguous arcs for us, but also teaching us a thing or two about filmmaking along the way.

The cinematography in Brosnan’s films is especially well done, helmed in large part by a man named Blaine Rennicks (“Sineater,” “Jacob Wrestling with the Angel”), but also by Brian O’Connor, the cinematographer for “Last Service.” The camerawork grows along the way through these films, as does Brosnan’s scriptwriting.

In “Wrestling with the Angel,” Rennicks plays with light and darkness to pleasing effect, switching shooting locations between a darkened corridor and sandy beach respectively. One shot on the beach between Brosnan and Hughes was doleful and sweet, and reminded me of a similar shot between Leonardo DiCaprio and Marion Cotillard in Christopher Nolan’s wonderful “Inception.” Wether or not Nolan – who has experimented with bizarre, dreamlike pictures before (see “Memento”) was an inspiration for Brosnan remains to be seen. But some similarities present themselves.

Brosnan also uses cinematography in his films to show introspection, as in the pensive “Forgotten Paradise,” which follows a lonely, alcoholic man (played by Charlie Ruxton) through the streets of Ireland during one day. During one shot, as night falls, the man takes a look into the camera – at us. Is it a warning, that perhaps he could be anyone of us? Is it a cry for help? Or is it something much simpler and sadder – a man looking out into the vast unknown, hoping to find someone who understands? We’re not to know. Brosnan wants us to be part of the film, and I found this to be one of the most intriguing shots across his four shorts.

I suspected, which was confirmed to me by Brosnan, that the theme of addiction runs through his films as a narrative tool. His full-length film “Con,” (2017), which I reviewed, deals with an alcoholic that returns to his hometown after returning from the abyss. In “Forgotten Paradise” and “Sineater” we are confronted with images of addiction whose victims are less lucky. In “Sineater” we find out the fate of one addict; in “Forgotten Paradise” we do not. And while “Con” was filmed as a mockumentary, these two are not, and offer imagery and music to imbue their message.

The soundtrack for both these films is done by a man named Jason Fernandez, and changes along the films. In “Sineater” it’s dark and morose, filled with synthesizers and low bass, highlighting the film’s desperation. However, in “Forgotten Paradise,” which also deals with addiction, Fernandez offers up a gentle, subtly beautiful piano score, along with lyrics written by Brosnan and sung by a woman named Cori Fernandez (Cori and Jason Fernandez also composed the music for “Jacob Wrestling with the Angel”). While the film is sad, the score is not, flirting with beauty and forgiveness in equal measure.

The acting across the four films is varied, from stellar performances to minimal, and those in between. Brosnan himself only appears in two out of the four – his first, “Jacob Wrestling with the Angel” and “Sineater,” in a very minimal role. Brosnan is an apt actor, and the expanded screen-time he received in his full-length “Con” shows capability. But his real talent lies in directing. He knows how to direct his actors, and his crew, which is no more evident than in “Wrestling with the Angel” and “Last Service.”

The film’s other actors, from Joe Mullins, Amy Hughes, Seán McGillicuddy, Charlie Ruxton, and Michael J. O’Sullivan all perform well, turning in the kinds of performances each picture requires. In “Wrestling with the Angel,” “Forgotten Paradise,” and “Sineater” these performances require minimal dialogue and facial acting, which the cast does well.

Writes one critic of the performances in “Sineater:” ‘none of the supporting cast can really hold a candle to Mullins’ performance.’ However, I tend to disagree. Mullins is good, no doubt about it. But I don’t feel he outshines McGillicuddy, or the film’s other players, in any sort of significant way. This is a credit to Brosnan’s directing and writing, who knows what he wants out of his film and casts the effort accordingly.

I haven’t talked about “Last Service,” saving it for last, as it is truly Brosnan’s crowning achievement on all fronts. From a directorial standpoint, it’s expert. It’s filmed in black and white for its majority, shot by a man named Brian O’Connor, and the duo let the camera, and its only actor, Stephen O’Connor, do the work.

“Last Service,” billed as a documentary of a gravedigger (O’Connor) as he remarks on his job, is expert, in everything from the cinematography, to the acting, to the bittersweet piano soundtrack, scored by Brian Lane. Brosnan stated to me that the film was inspired by speaking to actor O’Connor (who has 3 acting credits to his name, playing himself in two of them), stating that “…His life as a gravedigger is a beautiful subject because [O’Connor] is a very endearing person.”

However, documentary isn’t really what this film is, but rather eulogy – of both the dead the gravedigger speaks of, and the job this man performs. The film is comprised of one sided interviews – with only O’Connor talking, filmed in long shot, interrupted only by scenes of him doing his day-to-day routine, that makes the picture feel more than a documentary, but a moment captured in time.

I also like the admiration Brosnan puts into the message of this film. The gravedigger takes exceeding care of his work. Why not? Don’t we all? Does the carpenter, the lawyer, the doctor…or even the writer take any less care in his or her work? Society is quick to attribute its undesirable professions as such, and to devote little, if any, time to exploring them. Brosnan has done a service here, not in exploring blue collar work, but in refusing to label it as such. What the gravedigger does has purpose; and “Last Service” invites us in to this purpose with philosophy and realism.

O’Connor is really the gem of this picture, his speech realistic, mournful, and beautiful. In one scene, O’Connor talks about a variety of grave sizes – for adults, teenagers, children; and even though he admits a majority of graves are dug for people over middle age, his point is well taken: no age can escape death’s grasp. He further comments that infants and children’s burials hit the hardest. “You want to have a heart of stone not to be touched by it,” he narrates.

This film – wether the black and white presentation, the solemn score, or the exceptional talent by O’Connor, is Brosnan’s best work. It’s mature, decisive, final. It’s a footnote on the three films that proceeded it, and even the full-length “Con.” While Brosnan’s other films explored themes of addiction, sadness, and regret, “Last Service” acts a penance for those emotions. There’s a peacefulness in death, amidst its sadness, that Brosnan and O’Connor imbue with their respect for the gravedigger’s profession and those he serves. Last services and last rites are usually reserved for the Church. We seldom, if ever, think of the men or women who truly lay our loved ones to rest. “Last Service” gives us a face, a name, and a deference to those who undertake not this profession, but, in Brosnan and O’Connor’s eyes, this duty.

At the end of the day, Bertie Brosnan has produced four solid films here. Sure, they’re not perfect. Some, like “Jacob Wrestling with the Angel” wander a bit and run too long for the material, while others, like “Sineater,” could have used a little more dialogue and exposition to sell the story to us. With exception to Stephen O’Connor, the acting is good, but not superb, which is not the blame of their talent, but of screenplays written more for the camera than for actors.

But all in all, Brosnan has presented a series of films that do what independent films do best – they make us think, they make us feel, they make us question. During some moments you’re perplexed, during others intrigued, and during others still, truly moved. Wether or not you’re a fan of the indie circuit, or have seen “Con” and liked what you saw, you’ll likely be pleased by these four shorts. Brosnan has put more than time into these films, he’s put pieces of himself. If you only ever devour mainstream cinema, you may not find what you’re looking for here. You won’t find-fast paced plot or action. But you will find emotion, which is just a good a reason as any other.