There are times when we may encounter an artwork whose interpretation has to be derived from either one of several most applicable theories. A good example for this type of an artwork is the indie movie “Sinful,” a psychological thriller that, as any other film from the genre, functions as a puzzle. The theory I’m choosing to approach its interpretation is semiotics since it offers an analytical and descriptive method. Semiotics first originated in poststructuralism, which parts from structuralism but is more refined, and has more elaborated and inventive views on meaning. The main figure here was Roland Barthes, who used the famous apricot and onion metaphor to refer to the concept of meaning:

“If up until now we have looked at the text as a species of fruit with a kernel (an apricot, for example), the flesh being the form and the pit being the content, it would be better to see it as an onion, a construction of layers (or levels, or systems) whose body contains, finally, no heart, no kernel, no secret, no irreducible principle, nothing except the infinity of its own envelopes—which envelop nothing other than the unity of its own surfaces.”

Basically, what Barthes was implying here was that content is irrelevant to meaning: the only thing that is relevant is form. Although films rely somewhat on content as do other types of artistic expression (even abstract paintings, for example), it’s impossible to create content that hasn’t been already created. Intertextuality is the only reality of human thought: humans can’t create anything out of nothing. History of ideas is a history of recycling ideas: therefore, it doesn’t matter what is thought of or said, but how it’s done.

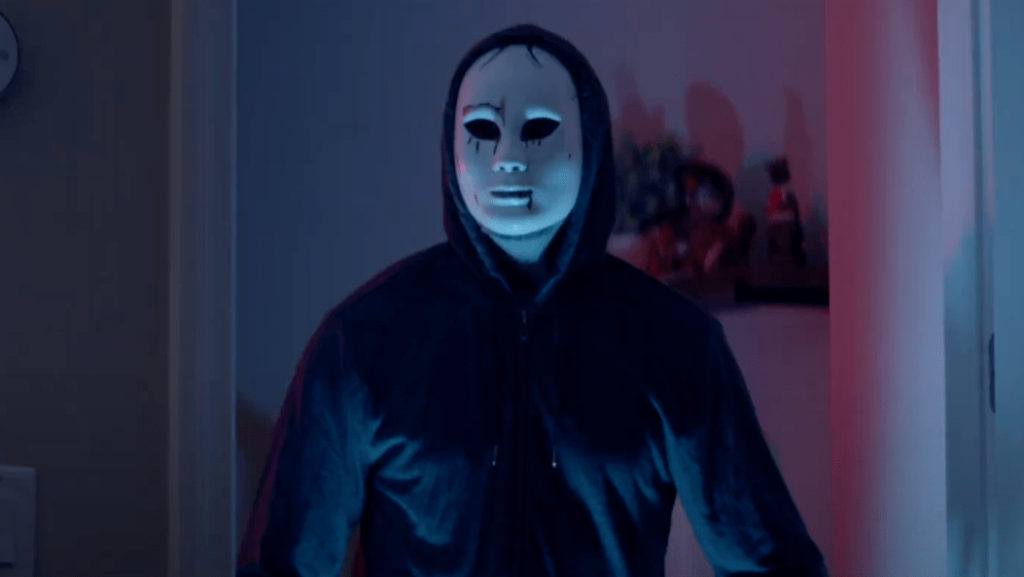

The content of “Sinful” can be reduced to a story about Remy and Salem, a newlywed lesbian couple, who have to spend some time hiding in a house of a family that’s spending a month abroad. Throughout the film, we are given some flashbacks and hints about why are they hiding and who are they waiting for: they’re waiting for Tyler, Salem’s friend who is supposed to bring the money they stole from Remy’s parents after murdering them. We understand that Remy’s brother was also murdered and that Remy’s father or stepfather used to be abusive to her. They both experience paranoia, hallucinations (probably due to a combination of drug and alcohol abuse), stress, guilt, and sleep deprivation.

It’s the way that segments are put together that blur the frontiers between what’s real and what’s not: it’s the form itself that carries all the meaning. The structure is multilayered like Barthes’ onion, like the metaphor of a Chinese box, like a Russian matryoshka doll. As in concentrical circles, each narrative contains another one, extends to it or points out to it. There are, however, some motifs and light motifs that permeate the narrative as a whole, passing through all its levels. An active participation and engagement from the viewer is required to solve this Hungarian cube.

A psychedelic atmosphere pervades: “Sinful” exudes hypersensitivity to sound, picture, and motion. (Anti)heroines lack psychological development, as in any film within the genre. Their final redemption is to realize what the reality is: usually more sinister than the one they’ve created.

“Sinful” is available on Amazon Prime and VOD. You can watch the trailer for “Sinful” below: