In “Eurocrime! The Italian Cop and Gangster Films That Ruled the ‘70s,” documentarian Mike Malloy interviews many filmmakers and actors who made the low-budget, ultra-violent, Italian crime exploitation movies of the 1970s called Poliziotteschi. Of particular interest to Americans, John Saxon, Fred Williamson, and Henry Silva are prominently featured. Malloy gives an overview of the development of the genre, the social context, and anecdotes about the personalities in front of the behind the camera.

According to the documentary, Italian genres of the 1960s and ‘70s germinated from the American and Japanese films. The new hip Italian post-war generation were mired in an ultra-violent, crime-ridden, economically depressed society; and, so, they were ready to rock hard. First came the Spaghetti Westerns, a genre arguably invented by Sergio Leone with “A Fistful of Dollars.” When the Spaghetti Western trend began to peter out, the Italian genre cinema was galvanized by new American films about urban decay, crime, and law enforcement disillusionment, particular “Dirty Harry” (1971) and the “Death Wish” series (starting in 1974).

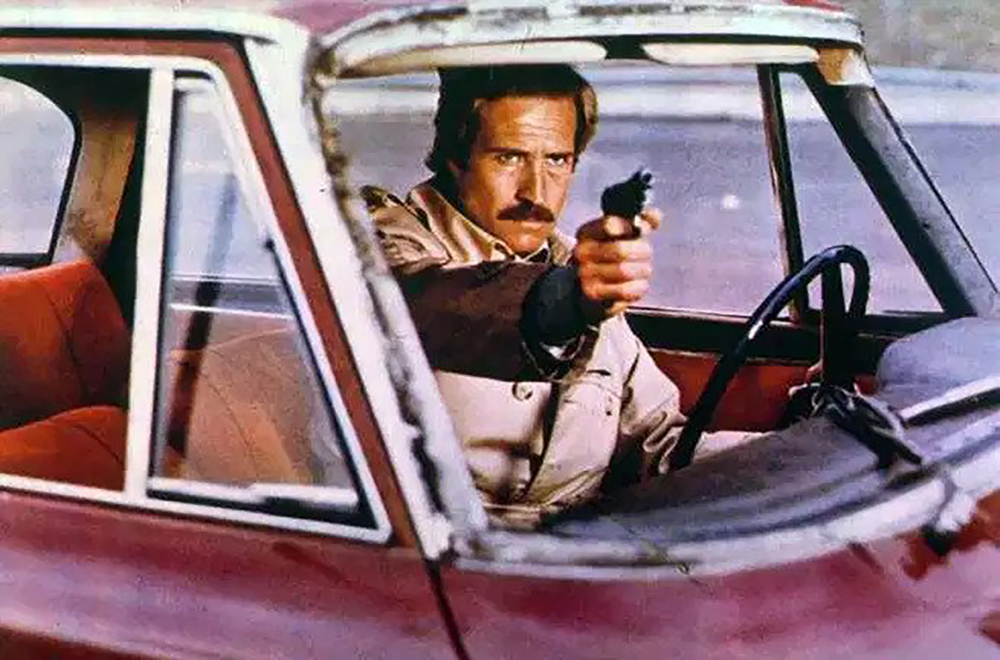

American rogue cop films and Italy’s Poliziotteschi were a weird counter-culture trend. Rather than being hippies who reject ‘The Establishment’ and all it suffocating rules, the protagonists are young police officers fed up with the way the establishment lets criminals run amok because of that suffocating ‘Due Process’ clause. So, to get the job done in the most destructive way possible, they show contempt for their superiors and flout the law itself to bring down the law-breakers. Sweet, sweet irony! And quite controversial in these times of unrest.

“Eurocrime!” could do with tighter, less “arty” frenetic editing and 25 fewer minutes. The documentarians try to mimic the snappy editing style in the genre they are exploring, but they would do the viewer a favor by letting us have more time to take in the information. This is not just entertainment, it’s film history. Nevertheless, it is worth watching for the film clips and stories about off-screen shenanigans, including how they managed to film on the home turf of the three Mafia groups – Costa Nostra, Camorra, and Ndrangheta.

I don’t know why Fernando Di Leo is not mentioned at all during the 140-minute run time. Di Leo was a formative influence on Quentin Tarantino’s filmmaking and his love of extravagant violence. If you want an entertaining and reasonably palatable example of this genre where the brutal misogyny is somewhat less atrocious, try Di Leo’s “Live Like a Cop, Die Like a Man” (1976).