To strike fear through the chords of familiarity, film narratives were created with an element of realism. American’s cultural obsession with—and love for—cars created an opportunity for storylines featuring the malevolent automobile. A trove of directors including, Steven Spielberg, John Carpenter, Elliot Silverstein, and George Bowers all featured vehicles as their embodiment of evil. Most of us see, hear, and even drive cars every day. So, what is it about cars that are scary enough to warrant a leading horror role?

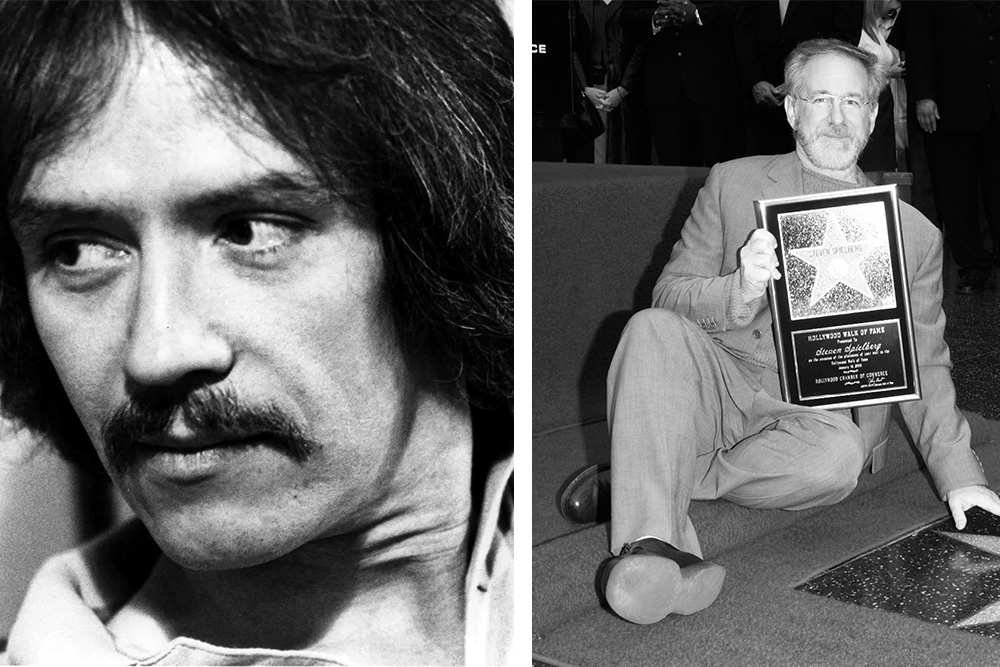

The obvious answer tells us that large, metal, objects hurtling towards us uncontrollably—or perhaps, even more sinisterly, controlled with the intent of maiming or murdering—are fatally terrifying. Modern horror films shine a light that highlights how and why these car characters are so scary. Horror films tend to split down the middle; one one side we see the unknown supernatural/paranormal, and on the other, the psychotic slasher with an unknown motive. Steven Spielberg directed “Duel” at the turn of modern horror in 1971, and John Carpenter directed “Christine” for release 12 years later in 1983. The films are very different in direction, narrative, soundtrack, and cinematography, but both feature vehicles as their demonic antagonists. One commonality is the hailing success of both films, which is evident from their cult status in modern horror.

*Note: this article contains spoilers for both films.

Two Iconic Directors: Spielberg and Carpenter

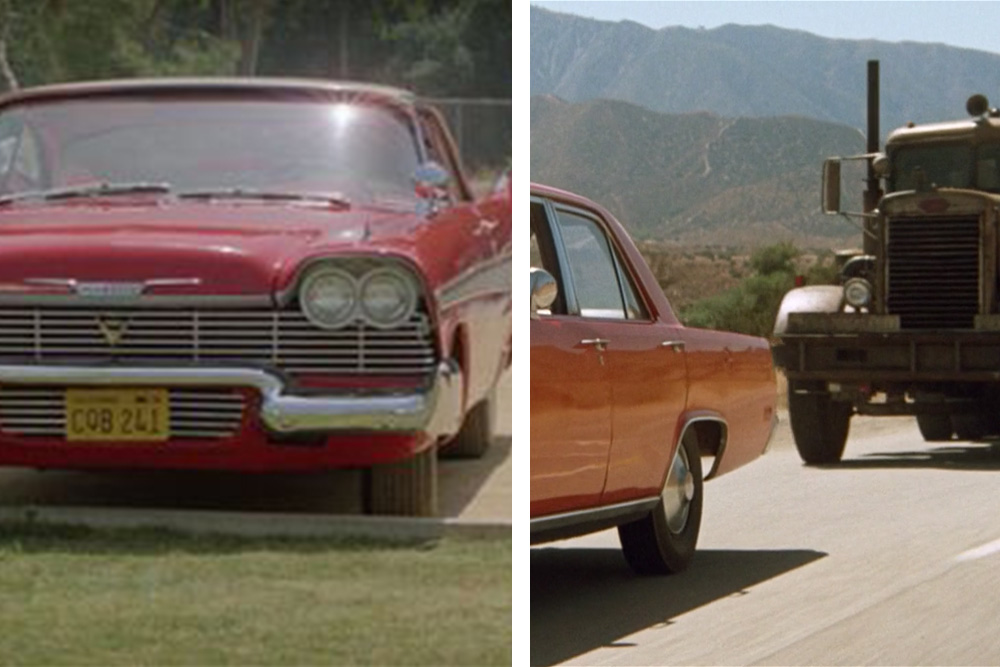

“Duel” follows a businessman, David Mann, who is commuting across America in his red Plymouth Valiant to meet a client. David overtakes a rusted out Peterbilt 281 tanker truck, much to the mostly unseen truck driver’s displeasure. After weaving in and out of each other’s paths, tensions are building, but the truck driver waves David ahead. Believing their highway spat is over, David pulls out and is nearly hit by an on-coming vehicle.

David is shaken up over being almost killed by the truck driver. However, there’s no respite for him as it becomes clear that the truck is intent on following him. The truck driver, playing with its prey, turns around to come back to taunt David when he can’t keep up. The cat-and-mouse chase comes to an end when David locks his accelerator with his briefcase and steers the car into the on-coming direction of the truck, before jumping out to safety. The car crashes into the truck and bursts into flames. The flames now obscure the truck driver’s vision as he plummets over the side of the canyon. The only sound of defeat is the prolonged horn from the truck as it descends. David celebrates on the side of the cliff, and the credits begin rolling over the sunset as he sits throwing rocks into the canyon below.

With the tagline “How do you kill something that can’t possibly be alive,” Carpenter released his supernatural take on the car villain through an adaption of Stephen King’s novel of the same name, “Christine” in 1983. The film opens at a Chrysler Corporation assembly plant in Detroit, where the hood of a newly assembled red-and-white 1958 Plymouth Fury crashes down and crushes the hand of a line worker inspecting its front end. Another worker climbs into the car to inspect the wheel, and the ash of his cigar falls onto the seat. At the end of their shift, the line supervisor notices the radio playing in the car. When he reaches to turn it off, the corpse of his colleague falls out.

The plot skips 21 years to follow an awkward and unpopular high schooler called Arnie (Keith Gordon), who buys a used, run-down, red-and-white 1958 Plymouth Fury called ‘Christine.’ What the seller fails to tell Arnie, is that his brother, his brother’s wife, and his niece were all either killed by, or died by suicide, in the car.

Not knowing the car’s past, Arnie begins to restore the car at a local do-it-yourself garage. When Christine promptly tries to kill Arnie’s girlfriend at the drive-in, it becomes clear the car seems to have a jealous and obsessive personality and a mind of its own. Although Christine isn’t the only jealous one; school bullies break into the garage one night to vandalise Christine. When Arnie finds out he is devastated, however he is surprised to watch the car quickly restore itself. Christine takes it upon herself to seek out the vandals and kill them.

Unfortunately, Arnie is not safe either: as Christine crashes through the do-it-yourself garage, Arnie is thrown through the windshield and impaled on a shard of glass. Mourning his loss, Arnie’s best friend, and ex-girlfriend, attack Christine with a bulldozer, but because of the car’s regenerative power, they must do this quickly enough to defeat her. As the film ends, the camera slowly zooms in on Christine’s remains, as the front grills begin to twitch.

Human vs. Supernatural Antagonist

Considering these two plots, each film is vastly different. The villain in “Duel” is the truck driver that chases down the protagonist, whereas the villain in “Christine” is the car itself that drives the protagonist down his own road to self-destruction and death. There is a conflict between the two drivers in “Duel,” however “Christine” seems to work with the main protagonist. “Duel’s” evil comes from a sadistic driver who is operating the truck, whereas “Christine” is the embodiment of evil. To dive into these comparisons at a greater depth, it’s important to consider the characterisation of each vehicle.

There is no paranormal element to the villain of “Duel.” Instead, the truck driver, played by prolific stunt driver Carey Loftin is IN the position of the slasher. In lieu of the symbolic slasher mask, the truck driver is concealed by the truck’s rusty front end with the big gaping iron grill and piercing, round yellow lights. Illegible number plates from all around the states adorn the bumper, claiming no specific home.

In keeping with the slasher characterisation, the truck driver uses the unconventional weapon of his own truck. The importance of unconventional weapons in slashers comes from the sadistic nature to maim and torture before killing, as well as the intention to vilify everyday objects. Typically, slasher villains are male, and their weapons are rife with phallic symbolism, although this might be a stretch when looking at a tanker truck. However, considering the power dynamic between the overbearingly powerful tanker truck, and David’s smaller less powerful red Plymouth Valiant is perhaps a foreshadow for Christine’s revenge.

There is no paranormal element to the villain of ‘Duel.’ Instead, the truck driver, played by prolific stunt driver Carey Loftin, is IN the position of the slasher.”

From the beginnings at the car plant, it is evident that Christine is a particularly malicious vehicle. There is a two-decade gap between this and Arnie’s ownership, although Christine’s checkered past does come to light to bolster this gap in time. The past held in these backstories cement “Christine” as a ghost story, as a supernatural entity that is tied to an object—in this case, a Plymouth Fury.

Arnie can drive Christine himself, but due to the spirited car’s free agency, it does not necessarily need a driver. Rather than the car being a property of Arnie, Arnie starts to become the car’s property. We see this in Arnie’s behavioural changes the longer he works on the car; he starts to slowly morph into a 1950s greaser with an arrogant and paranoid personality. This is significant as Arnie is a high-schooler going through his coming-of-age experience in the 1970s, not the 1950s, and so Christine’s influence is made obvious in this visual aesthetic.

A Feminist Viewing

As Christine is an object, the gendering of the car is exists on the idea of her. Historically, objects like vehicles have been given she/her pronouns. Traditionally in societal contexts, men have been the operators of machinery, and as such they feel an incessant need to look after and maintain their machines. This notion becomes attributed to the idea of the “looked after woman.”

In a feminist viewing, however, not only is Christine capable of operating independently, but the car can also repair and regenerate independently. Although the emotional grasp on Arnie’s influence can be clearly noted, Christine does not hold a sentimentality for Arnie’s life, made evident by his death. So, while Christine has feminine pronouns, and a feminine name placed on it, the car does not possess the traditionally stereotyped feminine qualities of nurturance, cooperativeness, or tenderness. Why? It’s a car. Instead, the film narrative exposes Christine’s qualities through possessive, jealous, disrespectful, and controlling behaviours. These qualities are all inherently toxic, and point towards a volatile relationship, rather than specific, stereotyped gender qualities.

Gender dynamics are not so transparent in “Duel” as unlike “Christine,” there is an element of spatial disparity. The truck driver remains mostly unseen, and becomes encapsulated by the image of his truck, whereas David is almost always shown through the perspective of the windshield. This decision creates an illusion of vulnerability; the truck driver is up in the safety of his cab, and David is hurtling along in a much smaller vehicle.

Spielberg uses a now hallmark wide-angle lens to harness fear through photographic realism. Spielberg arranged his shots in a deep focus, so the truck appears in the background as David’s car sits in the immediate foreground; for example, the camera shows David behind the wheel, as the truck appears in the distance through the rear-view window. To further this, Spielberg creates a mise-en-cadre where the radiator grill of the truck races towards the camera to suddenly take up the entire frame which creates an overwhelming sense of spatial domination. By using these techniques, Spielberg created a kinetic energy and panic brought about by a fast-approaching entity.

The Sound of Horror

The underlying tension in “Duel” is something we can both see and hear. As noted by the truck driver’s role of ‘slasher,’ “Duel’s” sonic narrative leans closely to slashers that came before it. Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho” (1960) is often regarded as the mother of all slasher films. A huge component of that film’s success comes from Bernard Herrmann’s music score; this is particularly true of the lethal, stabbing strings that accompany Bate’s knife in the killing of Marion.

Billy Goldenberg composed “Duel’s” score during filming, due to the tight schedule, and so Goldenberg was hugely influenced by the film’s location—namely, Soledad Canyon. There would be no direct sound effects or music cue to accompany the truck driver, so the truck became the audio source of terror. To understand the nature of the truck’s noise, Spielberg had Goldenberg ride along in the truck, driven by Loftin. Although terrified by these rides, Goldenberg managed to compose the complete score in one week. He would feature strings, harp, keyboards, and heavy use of percussion instruments and Moog synthesiser effects.

The synthesizer became popular throughout classic horror films, as the otherworldly tones sound like no familiar instrument. Modern horror started to move away from the conventions of film music from an orchestra. However, in stripped-down orchestral fashion, Goldenberg created a sense of impending doom through the low tones of the truck’s hum. The juxtaposition of David’s radio melody, suddenly cut over with the visuals of the truck’s thundering tires on the ground as they race after him, adds to the constant feeling of paranoia in the film. However, the radio acts as its own audio source for terror, particularly by gradually upping the tempo and pitch during critical times of the chase.

Contemporary horror films are still an avenue to explore societal themes, of which mass-motorisation is a prevalent topic; so perhaps there’s still room for an electric nightmare.”

The radio in “Christine” is as killer as the film’s soundtrack. Carpenter’s composing skills create stylistic consistency throughout the sonic narratives in his filmography. Carpenter created “Christine’s” score with fellow Composer and Sound Designer, Alan Howarth. Although he admittedly doesn’t think much of synthesizers, Carpenter has inspired many electronic musicians through his film music. “Christine” is no exception, as most of the music cues electronic synth based.

A Soundtrack to Match the Mood

Carpenter is a good fit for a King’s adaptation, as they both have a penchant for American youth subcultures. The “Christine” soundtrack reflects this, as it features contemporary pop-rock tracks including George Thorogood & The Destroyers’ “Bad to the Bone,” Buddy Holly & the Crickets’ “Not Fade Away,” The Rolling Stones’ “Beast of Burden,” and ABBA’s “The Name of the Game.”

While set in 1979, the soundtrack encompasses then-popular contemporary rock/pop songs, as well as 1950s rock-n-roll. This blend creates a sonic link to Arnie’s late ‘70s high school experiences and Christine’s own timeline. This is a common sonic feature of horror films that have a paranormal element. The timeline of the physically present characters and ghostly entities of the past are placed on top of the other. There is no ‘human’ element to Christine; this also shown through the sonics of her re-generation.

The sound effects are typical sounds of bending, cracking, and smacking of metal. While there’s a strong, pulsating, percussive element to the “Christine” theme, the beats are not reminiscent of a heartbeat sound. This could be an indicator of Christine having a particular human soul.

“Duel” and “Christine” are two horror films that use the character of the malevolent automobile, but through distinct sub-genres of modern horror that guide their direction, narrative, soundtrack, and cinematography.

Final Thoughts

Modern horror films tend to show good triumphing over evil by the end. Though slasher films are notorious for not concluding their endings, “Duel” shows David triumphing against the evil truck driver. However, the answer to “Christine’s” question, “how do you kill something that can’t possibly be alive?,” is much bleaker if the final shot is anything to go by.

Of course, “Duel” and “Christine” sit among a plethora of modern horror films that give horror autonomy to vehicles. While cars are still prevalent in 21st Century horror, they tend to take a back seat to the main narrative. For examples, take the “Duel”–esque truck chase at the start of Victor Salva’s “Jeepers Creepers” (2001) and the paranormal activities of the ghostly hitchhikers in Jean-Baptiste Andrea’s “Dead End” (2003). Contemporary horror films are still an avenue for exploring societal themes, of which mass-motorisation is a prevalent topic; so perhaps there’s still room for an electric nightmare. For now, though, the modern horror classics will live on through their cult status.

*”Christine is currently available to watch on Hulu via subscription or free trial. “Duel” is available to stream via Amazon Prime.