Despite these differences, the tone and style remain the same. Both films feature infamous Hitchcockian markers: camera movement that mimics character perspective, framing to maximise anxiety and fear, the use of darkness to indicate impending doom, climatic plot twists, and the restriction of action to single plot location to increase tension. By keeping his style consistent, we’re left with the suggestion that Hitchcock wasn’t concerned by his own directing style. So, why remake the original film?

During an interview and conversation on the two versions of “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” with the French filmmaker François Truffaut, Hitchcock remarked that, “Let’s say the first version is the work of a talented amateur and the second was made by a professional.” Unaffected by the whims of American humour, Hitchcock kept his typical British dryness throughout his time in the states, so perhaps, this quote can be taken with a pinch of salt. With a career spanning six decades, it is hard to envision Hitchcock as an ‘amateur;’ however, the two versions of “The Man Who Knew Too Much” give an interesting insight into the differences between the British film industry and the American film industry.

Birth of a Suspense Legend

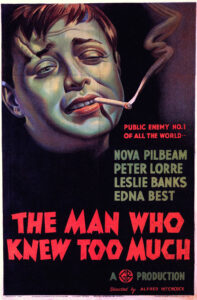

Born on the 13th of August, 1899 in London, Hitchcock started his career as a title card designer during the silent era of film. By 1929, he was the director of the first British “talkie” with his thriller drama “Blackmail,” following the rapid development of sound films over in America, which all started with Alan Crossford’s “The Jazz Singer” (1927). Putting the original version of “The Man Who Knew Too Much” aside, Hitchcock then helms two thrillers, “The 39 Steps” (1939) and “The Lady Vanishes” (1938), two of the greatest British films of the 20th Century. Perhaps not considered ‘the greatest,’ but the 1934 version of “The Man Who Knew Too Much” is one of Hitchcock’s most successful and critically acclaimed films from his British career.

Sitting on top of this hugely successful British career, Hitchcock was convinced by the American film producer, David O. Selznick, to make the move to Hollywood on a seven-year contract in April 1939. Hitchcock cautiously approached American film culture, starting with “Rebecca” (1940), starring British-American actor Joan Fontaine. The film was set in a typical Hollywood post-card inspired English seaside town in Cornwall. 16 years later, Hitchcock would release the 1956 version of “The Man Who Knew Too Much.” This comes out of his ‘peak years,’ which are generally considered as the years in between 1954 and 1964.

Some of the 1956 version’s biggest critiques show a nostalgic penchant for the original version. For instance, John McCarten of The New Yorker, claimed it was “unquestionably bigger and shiner than the original” but “it doesn’t move along with anything like the agility of its predecessor.” However, perhaps the second version was slightly overshadowed by Hitchcock’s other films from the same time frame, like “Rear Window” (1954), “Dial M for Murder” (1954), “Vertigo” (1958), and “Pyscho” (1960). That said, “The Man Who Knew Too Much” (1956) did well at the box office— however, this could be another reflection of how well Hitchcock films were doing during his ‘peak’ period of American filmmaking.

Perhaps not considered ‘the greatest,’ but the 1934 version of “The Man Who Knew Too Much”is one of Hitchcock’s most successful and critically acclaimed films from his British career.”

Now that we have a brief understanding of Hitchcock’s British and American career successes, back to the task at hand—how does “The Man Who Knew Too Much” encapsulate the ideals of the American and British film industries?

British and American Influence

The backbone of any film is undoubtedly production—money makes the world go around, right? Production must work with the Box Office in mind. Hollywood holds a particular international audience, whereas the British industry is much more modest when it comes to international recognition. American studios have had their own production facilities and subsidiaries in the UK from the early 20th Century, starting with Warner Bros., who acquired Teddington Studios in 1931 with the intent to produce ‘quota quickies.’

This was a helping hand for the British film industry, as Warner Bros. were working to the Cinematograph Films Act of 1927—an act implemented by the British Government to stimulate the declining British film industry. Other American studios that followed this act include Paramount-British Productions and MGM-British.

Now, despite this help, the British film industry’s relationship towards Hollywood is slightly more complex in attitude. This mainly comes from the understanding that the size of the British cinema market makes it impossible for the British film industry to produce a stiff-upper-lip Hollywood-esque production without American involvement to help fund the costs. Take, for example, Peter Cattaneo’s British Comedy “The Full Monty” (1997), which is set in working-class Sheffield, England. The praise for this went to the British industry, but because the “Full Monty” was entirely financed and distributed by the Twentieth Century Fox, the film’s profits went straight over the Atlantic to America.

Now it is probably no surprise to hear that Hitchcock’s British production of “The Man Who Knew Too Much” (1934) had an estimated budget of £40,000 (approx. $58,000), which pales in comparison to the American production of “The Man Who Knew Too Much” (1956) with a $1.2 million (approx. £846,000) budget. Of course, there are many considerations when setting a film budget; but ultimately the budget depends on what the company can afford, which influences production decisions.

Casting Decisions and ‘The Hitchcock Blonde’

One such decision is casting—and I’m not talking about Hitchcock’s cameos (although, of course he features in both versions). Many actors from around the world aspire to act in Hollywood, including those in the British film industry. British actors who have achieved international fame and critical success include Julie Andrews, Christian Bale, Helena Bonham Carter, Sean Connery, Kate Winslet, Emma Thompson, Colin Firth—and there are many, many more.

The first British actor of leading lady status to win a major American film contract with Paramount Pictures was Madeline Carroll. Her international success came from Hitchcock’s “The 39 Steps” (1935) which iconised her as the first ‘Hitchcock blonde.’ The notion of this ‘Hitchcock blonde’ is a character archetype which captures the restructuring of the submissive, domestic ‘good girl’ image. The character fits the appearance of a perfect icy-cold blonde model; however she is a ‘modern’ woman who—despite her clean wardrobe—is complex in character.

Both versions of “The Man Who Knew Too Much” (1934 and 1956) feature a blonde-haired leading lady. British actor Edna Best plays Jill Lawrence in the 1934 version; Doris Day is Josephine “Jo” Conway McKenna in the 1956 version. Despite both having blonde hair, Day’s character encapsulates the typical ‘Hitchcock blonde’ archetype given her prominent role in the narrative. While Best had a good film repertoire, Day’s position in Hollywood shot her to stardom with nominations for the Academy Award for ‘Best Actress’ (from her role in Michael Gordon’s 1959 “Pillow Talk”). Of note, the film narratives of both films have strong female characters that ultimately save the day.

The 1934 of “The Man Who Knew Too Much” version follows Bob and Jill Lawrence, a British couple on holiday in Switzerland with their daughter Betty Lawrence. While at the hotel, they befriend a Frenchman called Louis Bernard. During a chalet party, Jill is dancing with Louis when he is suddenly shot. Before he dies, he manages to tell Jill where to find a note intended for the British consul. It is Bob who reads the note, which warns of a planned international crime.

The mysterious criminals kidnap Betty to use as leverage to blackmail Bob and Jill into silence over the note. Bob and Jill return to England, unable to contact the police. However in England they manage to discover the plot to shoot a European head of state during a concert at the Royal Albert Hall. Jill manages to foil this by screaming at the critical moment to throw off the aim of the shooter. They follow the criminals to their hideout being the temple of a sun-worshipping cult. Bob enters, is caught, and ends up a prisoner alongside Betty. However, Jill has called the police who surround the building. The policemen, in classic Hitchcock fashion, are incompetent; it is Jill who shoots the criminals allowing the police to storm the building to reunite Betty, Bob, and Jill.

Updated Production, but Same Story?

The 1956 version of the film shows Dr. Ben McKenna and his wife Jo Conway McKenna, and their son Hank McKenna traveling from Casablanca to Marrakesh, when they meet a French man called Louis Bernard (heard that name before?). Jo is suspicious of his many questions and evasive answers. Moving on, they meet a friendly English couple called Lucy and Edward Drayton. The McKenna’s go on a trip to a Moroccan market with the Drayton’s, and see the police chasing a man. The man is suffering from a stab wound in his back; he approaches Ben, and it becomes clear that it is Louis in disguise.

ALSO READ: ‘Buff Tributes—Remembering Sushant Singh Rajput, a True Performer

Before dying, Louis manages to tell Ben that a foreign statesman is the target of assassination in London (of course); therefore, Ben must tell authorities about “Ambrose Chappell.” Lucy takes Hank back to the hotel, so the three adults can go to the police station. However, at the police station, Ben receives a threatening phone call; Hank has been kidnapped and is being used as leverage to blackmail the McKenna’s into silence (sound familiar?). Edward goes to ‘locate’ Hank; after all, he was left in Lucy’s care.

When the McKenna’s arrive back at the hotel, they find that the Drayton’s have checked out, which leads to the realisation that the Drayton’s were the couple that Louis was after. Ben and Jo leave for London, in search of Ambrose Chapel, which Jo realises is a place, not a person. Arriving at the chapel, Edward is leading the service. Ben confronts Edward after the service, but is knocked out and locked inside. The police arrive, and cannot enter the Chapel without a warrant. It’s here that Jill discovers the head inspector is at the Royal Albert Hall (again?) so the police take the McKenna’s there.

The Draytons take Hank to a foreign embassy. There a spy calls the police but the embassy is exempt from investigation, due to sovereignty. The ambassador at the embassy turns out to be the killer, who blames the Drayton’s for the failed attempt. In a desperate bid to find their son, the McKennas get an invitation from the prime minister. He asks Jo to sing “Que Sera, Sera” loudly in the hope that Hank will hear her. Hank does hear her and starts to whistle along which allows Ben to find him. Edward tries to escape at gun point; however, Ben kills him by hitting him so hard that he falls down the stairs.

So, as you just read, the plot has striking similarities. Families on holiday in foreign countries, a French intelligence agent who manages to relay his last words to the protagonists, an international crime plan, assassins, a kidnapped child, a religious location, the Royal Albert Hall, strong female leads, and incompetent police.

Concluding Thoughts

With such similar premises, it’s no wonder that critique of the 1956 version fell back on nostalgia. However, the plot becomes familiar and therefore predictable, which is not exactly ideal for a mystery thriller. However, the nature of American film and fast-moving technological developments make the 1956 version look and sound “shinier.”

The second version is about three quarters longer. This undoubtedly allows for more nuance within in the narrative; it features known actors in Hollywood, and the budget was bigger. This boosted production for both the visual and sonic aesthetics. So, rather than Hitchcock’s direction becoming fine-tuned, the biggest differences stem from the British and American film culture approaches. Regardless, looking at each film in their individual contexts, one thing is for certain—Hitchcock left a legacy of mastery in both countries.

*Citations for this article are as follows: “Hitchcock’s film career:” Allen, Richard; Ishii-Gonzalès, S. (2004). “Hitchcock: Past and Future.” Routledge AND, Chandler, Charlotte (2006). “It’s only a movie: Alfred Hitchcock: a personal biography.” New York: Applause Theatre & Cinema Books. “The Truffaut interview:” Truffaut, François (1983) [1967]. “Hitchcock/Truffaut” (Revised ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. “British Film History:” Warren, Patricia (2001). “British Film Studios: An Illustrated History.” B. T. Batsford. “Full Monty” Comment: Brown, Geoff; “Something for Everyone: British Film Culture in the 1990s” in British Cinema of the ’90s, London: BFI Publishing, 2000. New Yorker Critic John McCarten: McCarten, John (May 26, 1956). “The Current Cinema.” The New Yorker: 119.