This Father’s Day, we’re presenting a list of screen dads who don’t necessarily fit the ideal of a model father. From what we see of them, these men don’t play catch or mow the lawn. One of these fathers is more likely to say, disappear for years, only to emerge from the desert, unwilling to speak. In these ten films, the lives and connected relationships of these fathers are given the complex treatment they deserve. That’s thanks both to the performances from these legendary actors and the daring directors who elected to tell these often heartbreaking, sometimes harsh, yet always honest patriarch portraits.

‘Penny Serenade’ (1941) – Directed by George Stevens

The formidable comedic duo of Cary Grant and Irene Dunne anchor this honest dissection of a struggling young couple. For an early Hollywood film, it’s unexpectedly moving; lacks many of the cloying, feel-good resolutions so prominent in that era. Grant is clueless as a young father (been there!) bringing up baby, especially in a scene where he tries to rock his son back to bed with an unconventional technique.

‘Bicycle Thieves’ (1948) – Directed by Vittorio De Sica

Practically since its release, De Sica’s neorealist masterpiece has regularly ranked as one of the greatest movies of all time. The plot is deceptively simple; it shows a day in the life of a father who lost his job and his bike, and he brings his son along to search for it. A pioneering film that cast mostly non-actors to maximum effectiveness, it still stands alone after all these years.

‘An Autumn Afternoon’ (1962) – Directed by Yasujiro Ozu

Speaking of straightforward plots, Ozu’s tale of a widowed father who is arranging a marriage for his daughter follows a long line of his films of focusing on family dynamics in pre- and post-war Japan. Chishu Ryu — who acted in 52 of Ozu’s 54 films — plays the father; and his natural reserve both disguises and heightens his grief, having lost his wife and soon, having to see his daughter leave. Ozu died less than one year later; this color film is an appropriate elegy for one of the most restrained and important filmmakers of all time.

‘High and Low’ (1963) – Directed by Akira Kurosawa

Kurosawa remains Japan’s most famous filmmaker, with a style and scope that couldn’t have been more different than Ozu’s. Still, many of his characters’ preoccupations surround family and duty, and this taut noir is one of his towering achievements. Toshiro Mifune — who appeared in 16 Kurosawa films — plays a wealthy shoe executive negotiating the return of a son. It’d be impossible to elaborate without spoilers; and this a film that finds a way to consistently raise the stakes for its 143-minute run-time.

‘All That Jazz’ (1979) – Directed by Bob Fosse

Joe Gideon (Roy Scheider) is many things in Fosse’s thinly-veiled autofiction, and fatherhood seems low on his list of priorities. Though, each time I watch this Palme d’Or winner (it shared the prize with Kurosawa’s “Kagemusha”), it grows; it looks less like a Fellini rip-off and more like a gloriously unwieldy melding of genres. There’s plenty of dancing, drugs, death and music; but the most memorable scene is Gideon’s daughter (played by Erzsebet Foldi) and girlfriend (played by Ann Reinking, who dated Fosse) performing “Everything New is Old Again” to cheer him up after his latest play flops.

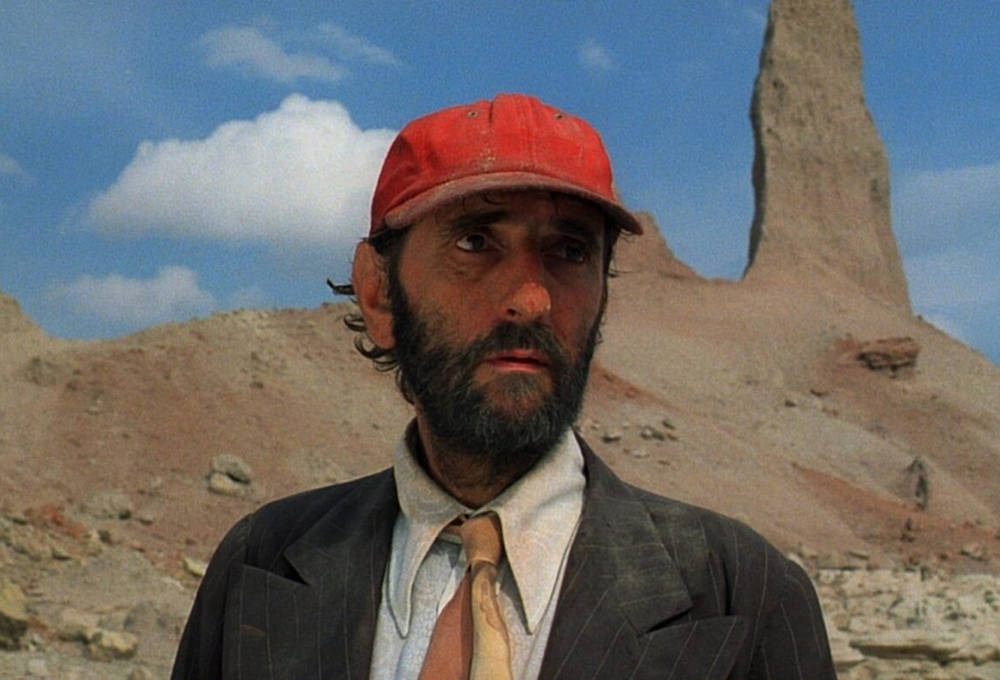

‘Paris, Texas’ (1984) – Directed by Wim Wenders

Another Palme winner, Wenders’ beloved film gives us one of the most memorable and troubled father figures in film history. Harry Dean Stanton, superb as always, plays Travis Henderson; he wanders out from the desert and back into his son’s (eight-year old Hunter Carson plays the son) life. This is presumably with the intent of reuniting with his wife (Natassja Kinski). This was not Wenders’ first or last film directly or indirectly related to fatherhood conflict; but it’s the most accessible thanks to the talent behind (Sam Shepard wrote it, Robby Muller shot it) and on (HDS, Kinski, and Dean Stockwell) the screen.

‘The Straight Story’ (1999) – Directed by David Lynch

So, David Lynch made a Disney film. What’s the punchline? Those of us who were used to the mind-bending, violent, and non-linear Lynchian nightmares might not expect such a tender and reflective drama about an aging man (Richard Farnsworth) who rides his tractor hundreds of miles to see his sick brother (Harry Dean Stanton… again!). Farnsworth’s relationship with his daughter Rose (Sissy Spacek) is key to the film, as her own troubles catalyze her father’s decision to break the silence with his brother.

‘Magnolia’ (1999) – Directed by Paul Thomas Anderson

“Magnolia” is a go-for-broke, three-hour ensemble piece. Paul Thomas Anderson’s follow-up to “Boogie Nights” evokes Robert Altman in its focus on a group of interrelated characters in modern-day Los Angeles. And despite nods to other influences (Scorsese, Kubrick, Welles…Truffaut?), PTA makes this his own with bravura storytelling techniques and just-watch-this stylistic flourishes. Father-child dynamics are central to understanding the sense of loss and loneliness; whether its Jason Robards’ dying TV executive (with his son, played by Tom Cruise) or Philip Baker Hall’s philandering and possibly evil TV host, Jimmy Gator (and his daughter, Melora Walters).

‘The Royal Tenenbaums’ (2001) – Directed by Wes Anderson

Gene Hackman turns in a pitch-perfect performance as Royal, the predictably unreliable patriarch of the Tenenbaum family. This time, it’s Wes Anderson assembling a stellar ensemble cast, including Gwyneth Paltrow, Ben Stiller, and Luke Wilson as the children, Anjelica Huston as Royal’s ex-wife, and other Anderson regulars (Seymour Cassel, Bill Murray, Owen Wilson) in memorable supporting roles.

‘Toni Erdmann’ (2016) – Directed by Maren Ade

It’s best to approach this film with an open mind and no expectations, because no short synopsis could convey the joy and surprise of witnessing the arc of the father-daughter relationship in this German gem. Howard Hawks said that a good movie is three good scenes and no bad ones; and this film has so many great scenes in its nearly three hour run time — often Hawksian in comedic timing and payoff — that it’s also impossible to figure out which one to call out now. I can’t wait to watch this movie with my own daughter. Love you, Poppy!

Honorable mention: Jean Renoir’s The River (1951), Ozu’s Tokyo Story (1953), Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring (1960), Wenders’ Kings of the Road (1976), Lynch’s Eraserhead (1977), Costa-Gavras’s Missing (1982), Wes Anderson’s Rushmore (1998)