Literary adaptations are having a moment. In 2021, four of the year’s most acclaimed films — “Drive My Car,” “The Lost Daughter,” “Passing,” and “Power of the Dog” — were adapted from novels or short stories, and the mini-boon is continuing into this year. Two of the year’s most anticipated films, “Blonde and White Noise,” are based on seminal novels from Joyce Carol Oates and Don DeLillio, respectively, and the film versions are already commanding awards buzz and controversy.

We can’t wait for those films, but this had us craving some unheralded adaptations that have fallen out of favor either because of availability issues (three of these are not streaming anywhere) or a general lack of support from audiences and critics at the time of release. This list casts a wide net, starting with a Cary Grant blockbuster — based on a poem — that earned $2.8 million at the Box Office and ending with a Will Ferrell movie — based on a very short story — that made less money 71 years later.

‘Gunga Din’ (1939): Directed by George Stevens, based on a poem by Rudyard Kipling

Hollywood’s Golden Year was also a banner year for literary adaptations, as 1939’s two biggest hits (“The Wizard of Oz” and “Gone With The Wind”) were based on bestselling, epic novels. And then there’s “Gunga Din,” with its $1.915 million budget, which may very well have been the first big-budget adventure, no doubt serving as an inspiration for Spielberg’s “Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom” (1984).

‘Le Notti Bianche’ (1957): Directed by Luchino Visconti, based on a novella by Fyodor Dostoevsky

No stranger to adaptations, Visconti would later bring “The Leopard” and “Death in Venice” to the screen, although “Le Notti Bianche” was minimalist by comparison. The melancholy mood runs counter to the manic — and unreliable — first-person narrator in the novella, and the great Marcello Mastroianni in the lead role lends the film added credibility and depth. He plays a serious and reserved protagonist for most of the movie, making the playful scenes (his dancing!) all the more exciting.

‘The Heart is a Lonely Hunter’ (1968): Directed by Robert Ellis Miller, based on a novel by Carson McCullers

This sanitized version of McCullers’ daring debut feels more like an overwrought stage play, with long monologues and caricatures as characters. Still, the film is redeemed by Alan Arkin’s Oscar-nominated turn as Singer, the deaf jeweler who misses his best friend, and also, the sharp camerawork of the legendary cinematographer, James Wong Howe.

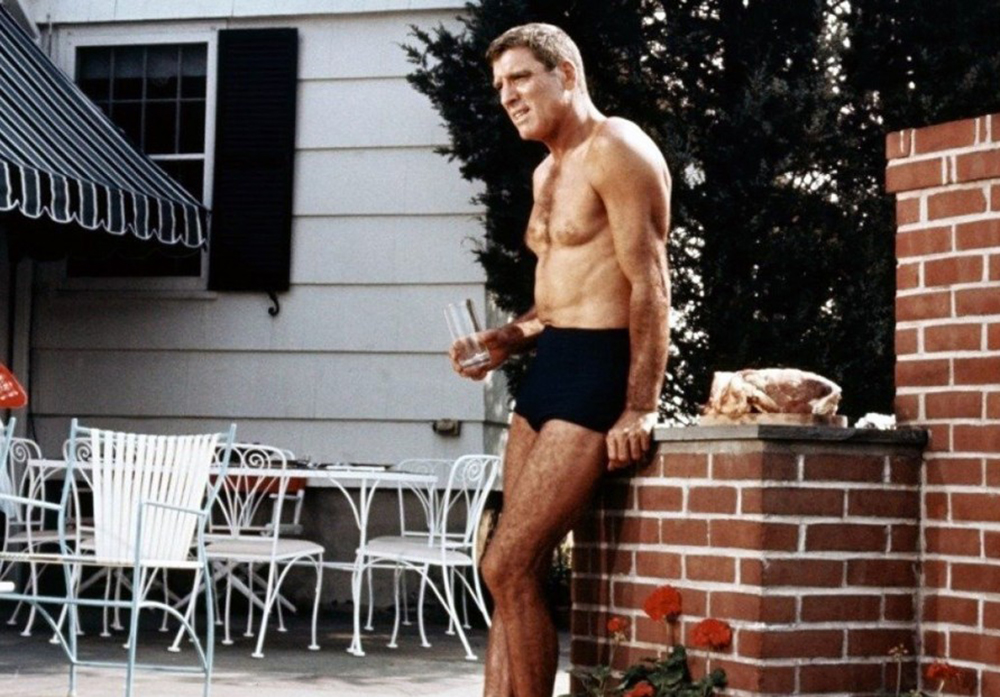

‘The Swimmer’ (1968): Directed by Frank Perry, based on a short story by John Cheever

Cheever’s brand of realism, focusing on domestic dysfunction, unrequited love and repressed desire, practically defined an era at The New Yorker, where he published more than one hundred stories throughout his career. Burt Lancaster, the iconic superstar, seemed an odd choice to play Neddy Merrill; yet he’s pitch perfect as the muscular, shirtless has-been on a delusional journey through his past.

‘Sometimes a Great Notion’ (1971): Directed by Paul Newman, based on a novel by Ken Kesey

It’s disappointing and bizarre that Newman’s woodsy sophomore feature as a director is so hard to track down. The film — based on Kesey’s second novel, after his sensation, “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” — is worth seeking out (check your library!), featuring Henry Fonda in a key role as the harsh and stubborn patriarch. Despite the considerable star power of the cast, it’s far from a commercial product, and still finds a way to subvert expectations with some beautiful and tender moments.

‘Looking for Mr. Goodbar’ (1977): Directed by Richard Brooks, based on a novel by Judith Rossner

This one isn’t easy to find either, with no streaming options and limited DVD availability. And that’s a shame, because it was a breakout movie not necessarily for its star Diane Keaton (who would win an Oscar that year for “Annie Hall”) but for Richard Gere and Tom Berenger who are both frightening in their roles as controlling obsessives. (Also: heads up for LeVar Burton in a bit part!) Rossner’s novel was based on a true story, and the screen version has a looming threat of violence and tragedy which makes the finale feel shocking, yet inevitable.

‘Chilly Scenes of Winter’ (1979): Directed by Joan Micklin Silver, based on a novel by Anne Beattie

Another New Yorker legend, Beattie wrote her first novel in 1976, and Micklin Silver’s screen version was originally released as “Head Over Heels” in 1979. Produced by the team of Amy Robinson and Griffin Dunne (who produced Martin Scorsese’s “After Hours”), it was rereleased under the new title once Beattie’s star had risen, and managed to turn a profit. John Heard evokes a suburban Woody Allen in an anxious, talky performance, supported by a stellar cast including Peter Riegart (“Animal House”), Mary Beth Hurt (“Interiors”) and Gloria Grahame (“In a Lonely Place”). Don’t expect to find this one streaming; best bang for your buck would be to buy this DVD double feature!

‘Tell Me a Riddle’ (1980): Directed by Lee Grant, based on a short story by Tillie Olsen

Tillie Olsen’s story is a masterpiece, spotlighting the troubled marriage of two elderly, unhappy people who are afraid of confronting both change and death. Lee Grant’s feature filmmaking debut is a bit awkward, telling a sad story that it knows is sad, deploying flashbacks and contrived moments of love and disdain. Still, it’s rare that a film gives an older couple’s relationship so much airtime. It’s also comforting to see David (Melvyn Douglas) and Eva (Lila Kedrova) as complex and argumentative people, not cute, elderly, or quaint grandparents.

‘The Castle’ (1997): Directed by Michael Haneke, based on a novel by Franz Kafka

Kafka gets the Haneke treatment, and the inimitable director is in a more playful mood than usual here, depicting the banalities and hostilities of bureaucracy. Haneke’s next film, “Funny Games” (1997) held nothing back, but this TV movie is far less severe. Both films star Ulrich Mühe and Susanne Lothar, an actual married couple, and their chemistry works well despite the movie not quite rising to the absurdity of the story.

‘Everything Must Go’ (2010): Directed by Dan Rush, based on a short story by Raymond Carver

Raymond Carver’s 1,600 word “Why Don’t You Dance” was the source material for this somber gem, a film that was destined to be overlooked upon its limited release. Will Ferrell, in a surprisingly restrained performance, plays a man who is stuck at rock bottom and determined to crawl out by living on his front lawn and courting his married neighbor Samantha (Rebecca Hall). It’s tight and fast-paced, stripped to the bone like so much of Carver’s prose, portraying heartbreak and alienation with ample doses of compassion and humor.