Andrew Dominik’s adaptation of Joyce Carol Oates’ novel, “Blonde,” often tethers the thin line of provocation and exploitation to a fault. However, when the film erupts into surrealistic Lynchian territory, particularly “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me,” “Mulholland Drive,” and “Inland Empire,” it tells a fictitious tale of one of Hollywood’s biggest icons. It intertwines fiction and reality, dreams and nightmares — equally horrifying, devastating, and hypnotizing — exploring trauma, objectification, self-destruction, loneliness, and desolation through visually poetic and lugubrious vignettes, a lengthy almost 3-hour canvas, and a tour de force performance by Ana de Armas.

After fighting to do it for almost a decade, Andrew Dominik finally managed to make his film adaptation of Joyce Carol Oates’ critically renowned 775-page novel, “Blonde,” which is also loathed by plenty of people. This is also Dominik’s first feature film in a long while. This is not counting his two excellent documentaries with Nick Cave and his The Bad Seeds companion, “One More Time with Feeling” and “This Much I Know to Be True’s with Warren Ellis.

Bringing Marilyn, and a Controversial Novel to Life

In the novel, Joyce Carol Oates tells a fictionalized tale of one of Hollywood’s biggest icons, drawing on literary traditions of fairy tales and gothic novels to conjure it. She was obsessed with the mystery behind Monroe’s life, what was true and what wasn’t. Dozens of biographers have disagreed with the basic facts of the bombshell’s life. There’s a myth behind the person you saw on-screen, Marilyn (the goddess), and the one nobody saw, her off-screen persona, Norma Jeane (the vulnerable), and her armor, Blonde (the symbol for the parable of the stainless existence of the upper-class – the ideal image during that day and age).

Therefore, Oates wrote out of intrigue and fascination. This fictional piece rearranges and invents details such as foster homes, screen performances, medical predicaments, and relationships of Monroe’s life. It seeks a deeper poetic and spiritual truth to the tragic reality of a celebrated and desired star. Then comes Dominik, who is a brilliant filmmaker in my book. His style and panache are often brutal; his features primarily focus on masculinity and the falling apart of male friendships.

Yet, at their core, those films are tragedies. Blood is spilled while characters live and later die (one way or another) by their natures, appetites, longings, and fervor. And we see specs of his pet themes in his latest feature, “Blonde.” However, one thing is for sure: it’s a tragedy – a fictitious myth of self-destruction, despondency, desolation, agony, and objectification told through a long-winded canvas of almost three hours, and an astonishing dual-performance by Ana de Armas in its lead role. There’s no other definition for “Blonde.” It’s not a biopic; it’s a story of sheer cataclysm.

‘Blonde’ Focuses on Poetry Rather than Prose; Which Might Explain Some of its Cruelty

From the beginning, it portrays the lights and allure of the big-screen spotlight in black and white. It creates an image that will remain in your head throughout the film’s entirety as it represents turmoil amidst ascendence. Dreamy in its aesthetics, while nightmarish in its development, Dominik tells Joyce Carol Oates’ personification of Norma Jeane’s story by way of disjointed vignettes with a surrealistic aftertaste that “recounts her life” from her childhood (with her mentally unstable mother) to her tragic death, as she ascends to fame and descends into the inferno.

Dominik’s filmography focuses more on poetry rather than prose or grace, hence its cruel demeanor at its most tragic moments. “Blonde” is a challenging film to go through, one that is rigorous and unforgiving. It is a film that often tethers the thin line between provocation and exploitation to a significant fault. It’s a conveyor belt of tragic moments tied to one another, presenting almost as if devoid of hope.

Also Read: Feature: 8 Characters in TV and Film that are Allyship Goals

“Blonde” nearly reaches a trauma-porn state due to its extensive reliance on tragic events — with scenes of sexual abuse and excessive nudity that will have plenty of people crawling for the exits. This is the film’s biggest problem. Nevertheless, what keeps it from not reaching that position is the poetic nature of Oates’ storytelling mechanisms. And this is combined with Dominik’s pitch-black, without elegance, destructive style.

‘Blonde’ is Indeed a Woeful Tale

This makes the viewing experience feel like going through a meat grinder. It lingers through suffering as fiction and reality, dreams, and nightmares are rearranged. “But where does dreaming end and madness begin?” In Dominik’s “Blonde,” dreams don’t last long. They are destroyed by tragic experiences that deteriorate Norma’s self but thicken Marilyn’s skin. Madness, however, is always present. “Blonde’s” introduction is fueled by a fire in the Hollywood sign, signaling an entrance to hell; even Norma’s mother (played by Julianne Nicholson) comments that she wants to see hell closer, despite being forced to go back.

This forces the narrative to tell its woeful tale to the audience vigorously. It’s demanding, in its full definition of the word, but Dominik and De Armas fully control their craft. All of Dominik’s films partake in the Australian director’s own style.

Yet, in his latest, he adopts the techniques of a master at the craft to tell this story of dual natures, the malicious underbellies of the Hollywood zeitgeist, and maintaining a kind heart when everything is coming down to a tragic end: David Lynch’s, particularly his work in “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me,” “Mulholland Drive,” and “Inland Empire.” From the electricity and flickering of the lightbulbs to the hand sign on the alley pointing to the stage door, similar to the fable turned reality told to Laura Dern’s character in “Inland Empire.” The constant telephone ringing, as seen in Lynch’s short film series, “Rabbits,” Dominik creates an expressionistic and lyrical Lynchian picture to portray the duality of a woman. This shadow possesses Norma, along with her crown, blonde hair, and the vessel, the body trapped in a glass cage. This is Marilyn Monroe, interpreted as Laura Palmer.

‘Isn’t Love Based on Delusion?’

All Norma wants is for her to be loved and appreciated beyond the specter that’s possessing her: the wraith that created the “flawless” illusion of the Hollywood starlet. “You’re going to imagine that next to your own real body is the imaginary body of your own character, whom you’ve created with your mind.” These are the words that Norma uses to cast the spell for the deceptive possession. The fame and glory are there. However, the rest is a curse of its own that constantly breaks her heart and ours watching.

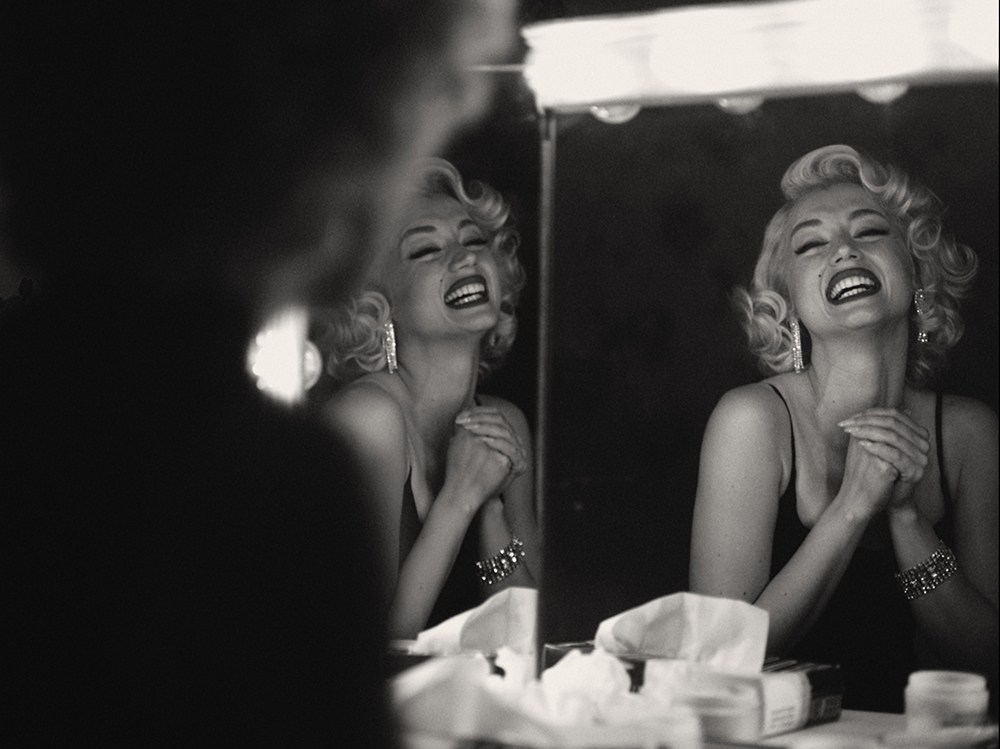

There are occasions in which Norma accepts the help of the wraith, confining it as a shield of armor. However, the audience notices that it is a prison in which she’s residing. Even though she’s beginning to witness that the persona she’s created is a prison, Norma searches for it. One of the most heartbreaking scenes in the film revolves around her makeup artist, Whitey (Toby Huss), putting on the makeup that transforms her into a platinum blonde actress while repeating the words: “She’s coming. She’s almost here.” And then, she looks into the mirror and sees the persona taking over for one last time.

Also Read: (Don’t You) Forget About How Iconic ‘The Breakfast Club’ is; an Examination of Hughes’ Masterpiece

Norma’s being drained by her own creation, a phenomenon of poisoning and self-destruction. “Isn’t all love based on delusion?” Marilyn’s mind is blurred by a “The Shining“-esque amnesia that doesn’t let her see reality anymore. The only thing she can see is the glamor and the spotlight paving her way into self-annihilation, manipulated by the higher-ups who never cared for her, seeing her as a commodity to fulfill others’ fantasies.

‘Blonde’ is Heartbreaking and Tragic in Equal Measure

Again, it is utterly devastating to see how each event in her life transpires. They end in heartache and with a lingering sensation of impending doom. It is all captured beautifully and sonically by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis’ magnificent and haunting score. This is especially when they use the Ellis’ howling in “The Bad Seeds” track off their album “Ghosteen,” “Bright Horse.” Dominik delivers almost three hours of provocation and psychedelic-yet-haunting poetry through various artistic distinctions. There are aspect ratio changes, changes in color schemes, and the glossiness of its production that transport the viewer into the story’s nightmarish and shapeless period. “Blonde” doesn’t capture reality nor the real Marilyn Monroe’s life; it showcases Joyce Carol Oates’ version of said icon.

That doesn’t excuse the ickiness of its synchronous exploitation. There are other ways to explore the objectification and mistreatment that Norma/Marilyn went through during her career than showing plenty of unpleasant scenes. Nevertheless, Dominik’s focus is on elevating the film’s aspect of distorting reality.

Also Read: Buff Tributes: Jean-Luc Godard, the Rebel Without a Pause

Plenty of beautifully-captured scenes showcase such distortion. A bed becomes the Niagara Falls, crowds chanting Marilyn’s name get extended, grotesque mouths, vomit is projected onto the camera, among others. “Blonde” is daring, equally horrifying, and hypnotizing in its storytelling by drifting from scene to scene dreamily and viscerally. I can see why people hate it; to their point, it is too cruel to bear at times and shocking, to say the least. However, I was utterly engaged with Dominik’s directorial heft and De Armas’ powerhouse performance. Like in “The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford” (2007), Dominik demands a lot of the audience. This is true of both its narrative structure, canvas, and appearance. Some will follow; others won’t. And there’s an understanding to both sides — the ones who love it and deem it a masterpiece or the others who detest it to a great extent.

‘Blonde’ is Hypnotic, but Difficult to Sit Through

Personally, I found myself liking the picture. However, I still have my drawbacks regarding some narrative decisions and its frequent tightrope walk between provocation and maltreatment. The Lynchian haze covers its looks (gorgeously shot by cinematographer Chayse Irvin). It haunts its sounds (lights buzzing, glass breaking, white noise crackling, cameras flashing). It puts the audience in a “Twilight Zone”-esque state for almost three hours, where you can’t escape or tune off.

Cinematic ventures like these aren’t often experienced nor presented in such a vast form. There is a scene that involves Adrien Brody’s Arthur Miller and De Armas’s Norma, which brought me back to the poem in Charlie Kaufman’s “I’m Thinking of Ending Things,” “Bonedog.” Of course, there’s no cinematic correlation with one another, but somehow, that poem emerged as I watched Domink’s “Blonde.” I kept thinking about the line: You sigh into the onslaught of identical days. The dictation of endless suffering caused by broken personas and possessions causes one to feel trapped in an endless cycle of despair. As the days go by, blurring into one another, Norma/Marilyn doesn’t change on the outside, yet they deteriorate on the inside.

Certain to be a Divisive Film Upon Release

“Blonde” is difficult to sit through because of its run-time and the themes and imagery being tackled and shown. It constantly weaves intense scenes of sheer suffering with collage-esque frames of reenactments — whether of Marilyn’s iconic pictures or photographs, and lines of contemplation. How desolate and stinging must it feel to be the epitome of the American Hollywood myth? She’s adored by many as they chant her name, though she never truly felt the impact of love. Watched by millions, though nobody ever got a chance to see the real her, only the presence captured by the spotlight and big screens.

By the time the end credits roll, you will be left puzzled for a good reason. What you have seen will remain in your mind for a long while. You won’t be eager to watch it again. Yet, you would like to discuss it. “Blonde” will be a divisive picture. Ambivalence will see its day upon release (more so than in Albert Serra’s “Liberté”, which also disturbed audiences across the world, while I remained entranced by what the Spanish filmmaker concocted). Many will fall onto the two-side argument of loath and love, while others won’t even bother to engage with it. Still, somehow, that makes the film even more interesting. Just like the autobiographers of Marilyn’s life debating each other over the simple facts, this movie will raise conversations between all watching regarding “Blonde’s” true nature and the layers of the story’s depiction of trauma.

“Blonde” is available to watch on Netflix starting September 28th.

Support the Site: Consider becoming a sponsor to unlock exclusive, member-only content and help support The Movie Buff!