Michelle Danner’s latest film, “Miranda’s Victim,” is based on a true story. It recounts the life of Patricia “Trish” Weir, who at age 18 was kidnapped and brutally raped by a man named Ernesto Miranda in 1963.

The aftermath of her ordeal, complemented with America’s legal system and a society largely turning a blind eye, could be the perfect encapsulation of the plight of numerous victims of sexual assault who have largely remained quiet all their lives. Director Danner, however, makes it clear in this movie: Trish was hellbent on changing the narrative.

And change the narrative she did.

Related Review: ‘Night Ride’ Tackles Gender Identity, Prejudice, and Sexism in a Darkly Funny (and Satisfying) Way

A Period in Time That Rendered Women Powerless Against Rape

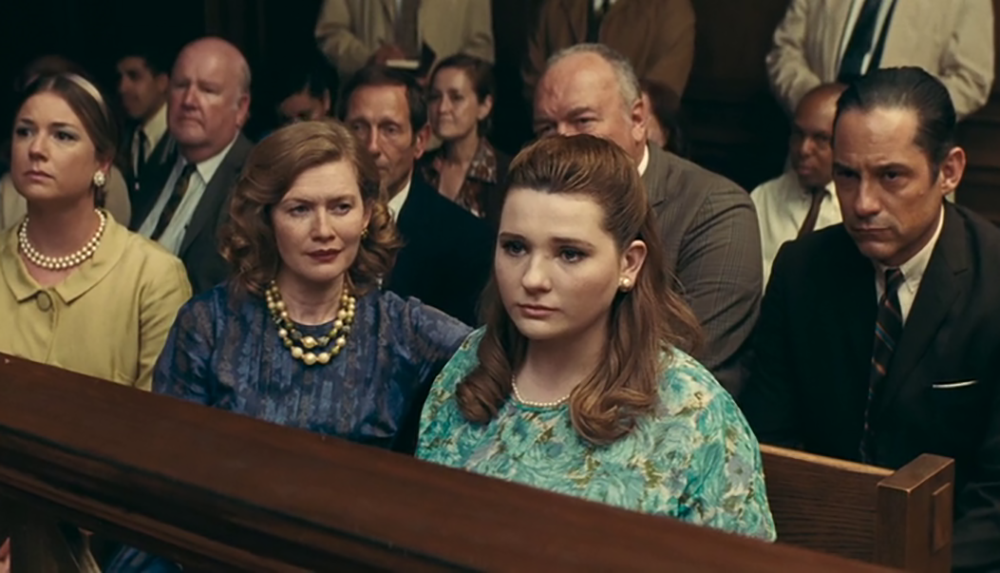

The film begins in 1966, when Trish (Abigail Breslin), now married and with a child, sees the news that the Supreme Court requires the police to inform criminal suspects that they have the right to remain silent—in what we now know today as the Miranda warning.

The movie flashes back three years prior, showing 18-year-old Trish and her mom (Mireille Enos) talking in the car about the proper way for women to behave. Her mother’s worldview of what being a good woman is involves wearing a smile to leave an impression to men at work; succeeding in secretarial school so Trish could meet successful men; and staying away from her who had a reputation as a ‘loose’ woman.

That fateful night, on her way home from a bus ride with a coworker she’s attracted to, Trish experiences hell at the hands of Miranda. Committed to putting her attacker in prison, Trish later on realizes how uphill the climb is. Because inasmuch as the public would definitely have polarizing opinions, her own mother expresses reservations.

While her sister Ann (Emily VanCamp) believes her completely, their mom doesn’t even believe her—at least not initially. That disbelief, however, masks an air of resignation that even if Trish was indeed raped, the police wouldnt do anything about it. Worse, Zeola believes that the spotlight such news would bring might even cost Trish a brighter future.

“I don’t want to see you become damaged goods.”

Basically, Trish has no other option but to suck it up so she can attract businessmen to be their wife, instead of someone men would avoid just because she’s the type of girl who accuses men.

An Eclectic Mix of Subtle and Explosive Performances Offsets an Uneven Direction

The screenplay from George Kolber and J. Craig Stiles struggles to maintain a clear focus, trying to cover as much ground as possible. As a result, the film a times vacillates between a family drama and a courtroom drama, with flashbacks of sexual violence sprinkled in. Danner, for her part, seems to follow suit with her direction, resulting in a movie that sometimes looks and feels tonally inconsistent.

Here’s where ‘Miranda’s Victim’ shines, however: As a world-renowned acting coach, Danner understandably has a very keen eye for terrific performances. From small roles to those that require masterful nuance, she manages to get the best out of her cast.

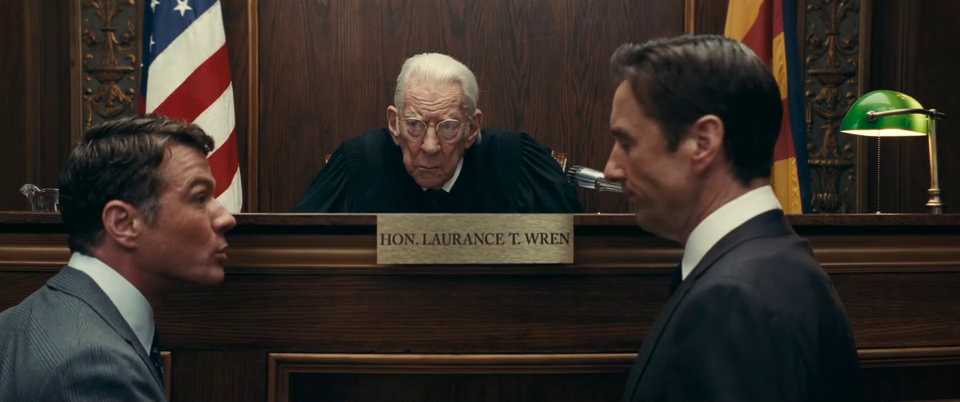

Of course, there’s the always-reliable Donald Sutherland as Judge Wren, whose presence alone commands a level of gravitas that’s both stern and paternal. Ryan Phillippe and Luke Wilson’s performances defending the opposing sides looks like a standard courtroom drama starring a hothead and a slick rick.

But, if there’s anything the movie successfully pulls off, it’s that it reminded audiences of how good Abigail Breslin is. Breslin, herself a victim of rape, is just heartbreaking here. Here’s hoping that she gets quality projects in the future that would showcase the very caliber that she can bring to the table.

‘Miranda’s Victim’: A Call to Action to Help Victims of Sexual Assault

A scene from the movie that I found amusing was when Trish snuck inside the theater where she works as a concession attendant. The movie people were watching, incidentally, was Atticus Finch’s closing argument in ‘To Kill a Mockingbird‘. Whether real or fiction, this was a nice touch by the filmmakers.

Here’s the bigger picture, though: according to the filmmakers, it took Trish 60 years to finally tell her story. And one could only imagine how she hopes her story would help others to gather the strength to stand up.

The film’s closing title cards include a glaring statistic:

Currently, for every 1,000 sexual assaults committed in the United States, only 5 result in a criminal conviction.

Along with a call to action followed by a hotline for victims of sexual assault, ‘Miranda’s Victim’ couldn’t be any more important today as an artform. Sure, it’s a little uneven on the direction but (commendably) very top-heavy with the performances of its cast; but ‘Miranda’s Victim’ manages to drive home the point of how several years ago, both the justice system and the social construct failed countless victims of sexual assault.

All other issues aside, nonetheless, this is an important film that’s small in scale but big in its intent. This is a galvanizing call for everyone to take part and take a stand: those who were told about it, to start believing; and those who were asked for help, to start acting.

‘Miranda’s Victim’ will have its premiere at this year’s Santa Barbara International Film Festival.

‘Miranda’s Victim’ will have its premiere at this year’s Santa Barbara International Film Festival.