To prepare for Ari Aster’s “Beau is Afraid” (2023), I watched Charlie Kaufman’s “Synecdoche, New York” (2008) for the first time in five years, motivated by the number of critics who invoked the latter in commentary on the former. The comparison holds at first glance: both films are ambitious, meandering passion projects. They’re written and directed by imaginative, beguiling auteurs who indulge in excesses of idea and style with varying levels of success. Whereas Kaufman refuses to romanticize his bewildering characters, Aster is staunchly in the corner of the harried, hard-luck Beau (Joaquin Phoenix) whose world builds, attacks him, then capsizes. Kaufman profiles a mad genius, tracking the self-inflicted decay of his mind and body while Aster pities Beau, blaming nature and nurture. Neither hero deserves suffering, but thanks to Aster’s perverse wit and garish aesthetics, it’s still a twisted treat to spend 180 minutes in his ghoulish, gonzo neighborhood.

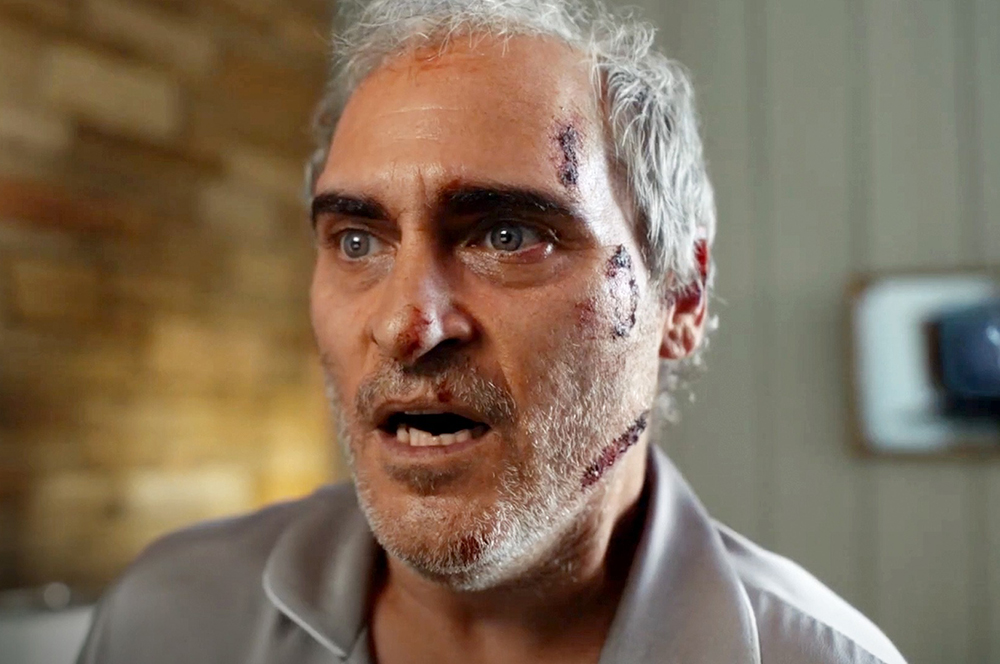

Poor Beau. He has all the reason in the world to be afraid, opening the film in his therapist’s office, describing his anxiety at having to visit his mother Mona (Patti LuPone) on the anniversary of his father’s death. That’s not the scary part. When he leaves the office, he walks home, and through a long tracking shot Aster reveals a dystopian city — with chaotic violence, rampant drug use, stray animals and children — that could’ve been lifted right out of Paul Verhoeven’s “Robocop” (1987). In the homestretch of his journey, Beau sprints to the front door of his apartment complex, barely escaping a rabid man in a full-body tattoo, who presumably was out for Beau’s blood. It’s a grim, unforgivable existence; yet Beau’s most visibility distraught when he has to warn his mom that he might not make it home because someone stole his keys and luggage.

Comparing Kaufman and Aster — Some Similarities

Beau deserves our empathy, but Aster doesn’t exactly present a convincing case for the alternative. Over in Schenectady, however, Kaufman’s Caden Cotard (Philip Seymour Hoffman) is a stellar prick, a self-involved, navel-gazing neurotic who maintains a singular focus on his art, deploying his McArthur (“genius”) Grant funds to construct a labyrinth stage play of epic proportions. Over the course of the film, Cotard contends with family abandonment, death, and his own body’s deterioration, and yet, Kaufman is even-handed in his presentation. This is no sob story. And when the audience might be ready to align with Cotard, the tortured artist distances himself from our sympathies with a condescending comment or egotistic behavior that no amount of his volunteer housekeeping could compensate for.

In other words, Cotard is a full and flawed character, a consummate and relatable jerk, equal parts perpetrator and victim. Given the chance to consider another perspective — it’s a sprawling, dynamic cast — Aster repeatedly doubles down on his unconditional support for Beau. Things just seem to happen to him, and the absurdity and tragedy mounts without adding much substance to the narrative or detail explaining Beau’s ultimate failure to launch. In flashbacks, we learn about his mom’s (the younger Mona is played by Zoe Lister-Jones) doting oversight and a childhood romance with Elaine (Julia Antonelli played the younger version, Parker Posey the older), but in middle age, what we see is the limited scope of Beau’s life. It’s never explained what he does for a living, and his meaningful relationship outside of Mona is with his therapist (Stephen McKinley Henderson), the only other person he had recently called.

‘Beau is Afraid’ is a Major Effort

Therapist — which is what the character’s called in credits and how he’s listed in Beau’s contacts — offers the first of the film’s many jolts. After exchanging pleasantries, he shocks Beau by asking, “Do you wish your mother was dead?” This character will return later, in a twist that’s less satisfying that it might sound. It’s rare that therapy humor — at the expense of either patient or therapist — comes off as fresh or original, and this film is no different. Here, Aster summons early Woody Allen shtick with some cheap laughs that don’t advance the plot’s tension. Guilty of that same sin is “Synecdoche,” where Madeleine Gravis (Hope Davis), plays a vapid, self-promoting psychologist, more fixated on selling her book than listening to Cotard. And the most regrettable result of scapegoating these characters is a waste of the valuable resources: Henderson and Davis.

Despite this lack of character development, “Beau is Afraid” is a major effort, a triumph of experiment (mixing in animation) and too-muchness (a monstrous one-eyed set piece which lurks in the attic). For what it lacks in cohesion it makes up for with scale; the screen sometimes feels too limited for Aster’s disorienting, restless vision. The chief concern here is Beau, and how he reckons (or ignores) his complicated relationship with his mother. But the film hurls Beau in so many different directions, from the suburban nightmare of a suspiciously caring couple (played by Nathan Lane and Amy Ryan) to a Shakespeare performance in the woods. The shocking climaxes of both sequences are textbook Aster. They’re among the most creative, colorful on-screen deaths in recent memory, with an ardent misanthropy which conjures from the belligerent arthouse provocations of Lars von Trier (“Dogville”) or Jean-Luc Godard (“Weekend”).

How Will Aster’s Film Fare Under Re-watch?

Still, there’s room for tenderness, especially in the animated scene, which exists in Beau’s imagination and grants him the companionship he lacks in reality. Phoenix, of course, is splendid throughout, and complaining that the director’s on his side could just be another way to compliment the ability of one of our finest actors to demand compassion. LuPone’s screen time is far too limited — relative to the space she occupies in Beau’s brain — but she’s an inspired casting choice. Mona’s the soul of the film, and the fire-redheaded matriarch dominates each minute she’s visible, combating Aster’s inflated caricature of Mona with an actual character of her own making. It would be no small injustice if the three-time Tony winner didn’t land her first Oscar nomination.

Having taunted and terrorized audiences with his debut “Hereditary” (2018) and then topping it with the brilliant “Midsommar” (2019), Aster has ensured that each subsequent film release will be an event. To call “Beau is Afraid” the weakest of Aster’s three films is a snap judgment, one that might evolve over time. Repeat viewings might alter that position, perhaps similar to how “Synecdoche,” on second viewing, struck me as accessible and controlled, a sad, challenging film that demands much from the audience but gives plenty in return. In other words, it’s therapeutic. Aster’s latest induces rather than quells anxiety, weaving in a pessimistic worldview and promising a grim resolution to Beau’s problems. It’s an unsettling trip, but also, a relief to know we have the option of entering and exiting Aster’s mind without complications. Too bad the same couldn’t be said for some of Kaufman’s earliest creations.