Do not be fooled by the singing, dancing, and occasional Bradley Cooper method outburst. “Maestro” is a serious film. It celebrates the staggering highs in the life of Leonard Bernstein (Cooper), but gives equal time to his faults, particularly surrounding his courtship and marriage to Felicia Montealegre (Carey Mulligan, who has top billing), a volatile partnership that bends, breaks, and then heals again. The film works like memory, lingering less on the tabloid moments which have taken on personalities of their own, and honing in on the grueling fights and heartbreaking medical diagnoses which are impossible to make sense of in the moment. A domestic melodrama clothed in biopic drapings, Cooper’s second feature might test patience when it turns into a chamber piece with the latch sealed, but it delivers on a promise to bring operatic flair and a meticulous eye to one distinct life’s fine print.

Bernstein Returning to Lincoln Center

Making its North American premiere at the New York Film Festival on Tuesday night, it’s hard to imagine a more evocative venue for the occasion than Film at Lincoln Center. In the film’s opening moments, a young, handsome and harried Bernstein gets that fateful call which summons him to what’s now David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center to conduct for the New York Philharmonic. He’s third string, but due to one conductor’s illness and another befallen by inclement weather, it’s young Lenny’s turn. Bernstein accepts calmly, then hangs up and howls out his bedroom window, drums on his lover’s firm buttocks in bed, then storms down the stairs from his building straight to the concert hall stage. It’s an exciting, exalting rush of energy, exhibiting the technical flair and long-take bravura of Spielberg or Scorsese, both listed as Executive Producers who were once attached to this project as directors.

But Cooper makes this his film entirely – as a director – and his pairing with Mulligan trades on their considerable chemistry and star power to turn uncommercial conceits into gripping entertainment. Centering a public figure who was a multi-hyphenate artist and bisexual in his personal life heightens the expectation for some juicy sex scenes and spicy gossip. And yet Cooper is even-handed in his appraisal, refusing to ignore the personal failures and conflicted private sex life. Naturally, the conducting scenes are dynamic, a pitch-perfect blend of pomp, sweat and circumstance. But, also, Bernstein the husband and father is held accountable, and it’s Mulligan’s layered portrayal – steely and playful, stern and committed – which doubles down on refocusing the film’s gaze away from the tornado which is Lenny, shunning the worn tropes of the put-upon wife by highlighting her moments of joy, and considerable artistic ambition.

There’s a moment when Bernstein approaches two friends – ostensibly a husband and wife – outside of Central Park in what had to be the winter months in the 1950s. Bernstein kisses them both on the lips, and leans in to tell their child “I’ve slept with both of your parents.” When Bernstein backs away and lets out a yelp (“I need to reign it in!”), Cooper takes over, breaking through this shield that protected Bernstein and hinting at the buried tension and accrued stress from keeping his love life a secret. It’s funny, sad, and in that sequence, speaks volumes for what another biopic might spend two-plus hours belaboring. And it makes the closing scene, with an aged Bernstein dancing with proteges at Tanglewood, solo cup in hand, head bopping at the sky, an odd kind of eulogy, complicating – and completing – the narrative about this man’s wayward journey.

The Agony of Life Through Joyful, Invigorating Direction

If there’s a glaring flaw, it’s when Cooper closes Lenny and Felicia in from the outside world. Or, that he makes their inner lives feel so limiting, which is a hard fact to accept given their dual residency in the city and the country, three healthy children, and artistic lives which shuffle them from concert hall to stage to screen. The exuberant moments mostly take place when Bernstein is at work, yet that’s not his entire existence. Towards the end of his life – and this film – Bernstein finds his voice, and the entire family is able to breathe their own air, which Felicia had reminded Lenny, was hard to do when he took up so much of it. In that fight scene, Mulligan’s a fierce contender, and her most cutting line – it involves the word “queen” – shocked and silenced Bernstein (and caused a collective gasp from fellow moviegoers).

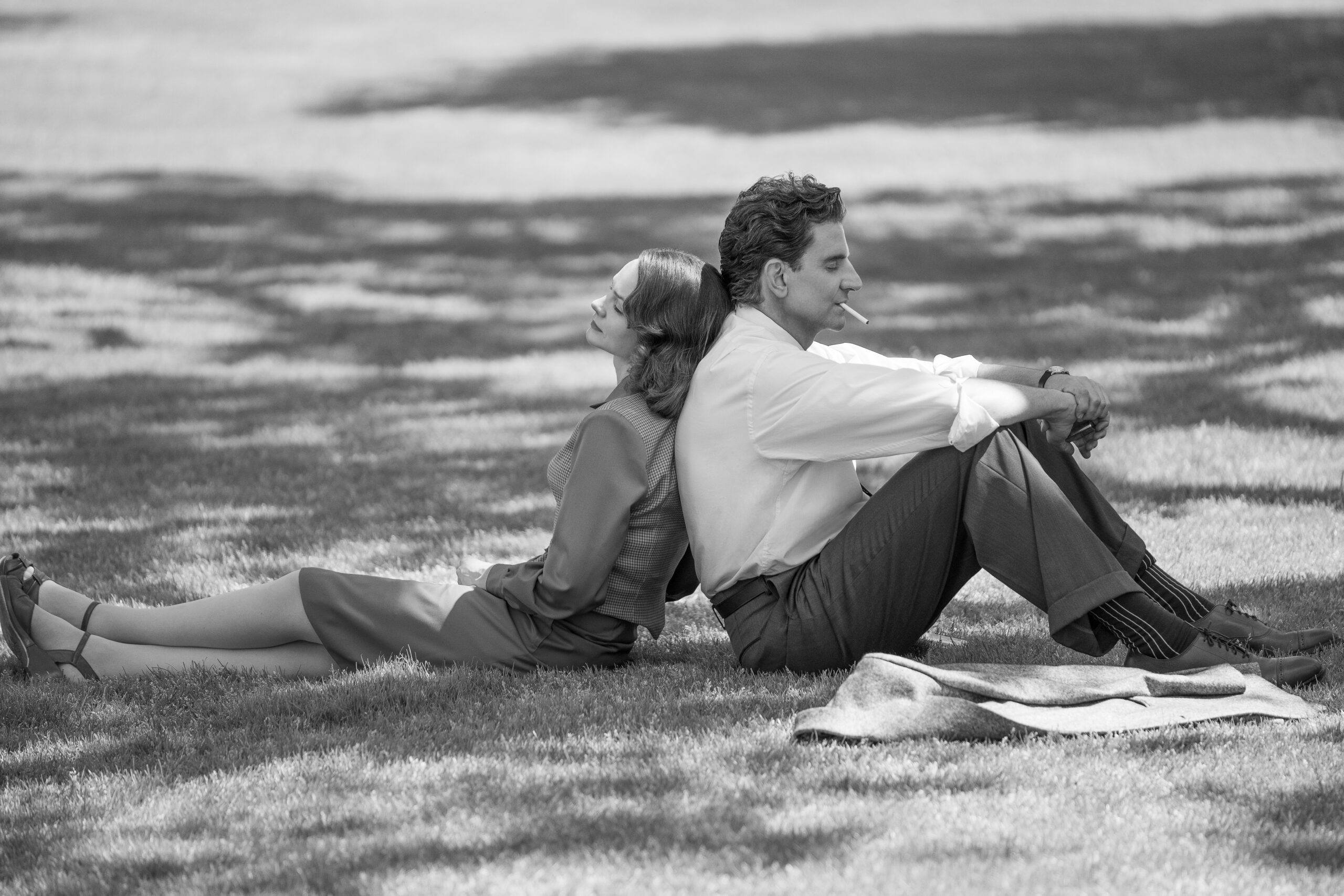

François Truffaut once demanded that “a film express either the joy of making cinema or the agony of making cinema.” With “Maestro,” Cooper’s articulating the agony of life through joyful, invigorating direction. When a mentor suggests to Lenny that he change his last name to Burns and tighten up his public and private life, Felicia has to know more, see the shenanigans. So, Lenny takes her to the theater. And in a surreal, fantastic twist, Bernstein transforms into a sailor from “On The Town” (1949), for which he composed the score. Cooper is no Gene Kelly. But that’s beside the point. There’s no light without dark, and it’s no coincidence that the film alternates between monochrome and color. In resisting convenient labels, avoiding heroes and villains, “Maestro” is a special statement, giddy with nostalgia yet unyielding when it dissects the way human beings hurt themselves and heal each other.

“Maestro” is currently playing at the New York Film Festival. The festival goes from September 29th – October 15th. Join us for continual coverage.