Robin Hardy’s “The Wicker Man” is basked in paganism, and a clear inspiration for Ari Aster’s unsettling “Midsommar.” That it bears the label of ‘horror’ might be a misnomer—even for 1973—as the film is more odd and spectacle-filled than scary. The film is revered as an example of good British horror, and the Scotland coast, thrown off from any worldly connection, offers memories of “The Lighthouse” and other isolate films. But, under it all, it is a film that embarks more on a religious war, so to speak; not of good vs. evil, but of Christianity vs. paganism. Its chief protagonist/victim Sgt. Howie (Edward Woodard) could be any one of those historical imperialists taught to us in school all those years ago.

Howie is a Puritan (not comparatively but actually), and arrives on the remote Scottish island of ‘Summerisle’ in search of a missing girl. He possesses an anonymous letter that said girl is missing, and early conversation with some of the island’s residents proves they are in no quick hurry to cooperate. Her name is Rowan Morrison, but no one in town has heard of her, even May Morrison, her supposed mom, who runs a town shoppe. Howie questions May’s young daughter of about nine in the back. She says she knows Rowan, but she’s a hare, who spends her days frolicking in the island’s fields.

Howie continues this sort of inquisition of the town’s denizen’s at a local bar. No one has heard of Rowan. They’re more interested in music and revelry than his concerns, which angers Howie. Wether he’s more angered by their lack of assistance or their customs—which are namely not Christian—is up for interpretation.

Horrors that Appear in Daylight

Like “Midsommar,” “The Wicker Man” keeps much of its happenings hidden in plain daylight, which adds an oddity to the proceedings. But where Aster’s film imbued a creepy air of psychedelics and bizarre custom, “The Wicker Man” offers plain-sight occurrences that are bizarre, but compared to films of today are not much to balk at. There’s a late-night orgy Howie sees on the way to his rented room, and a naked dance temptation by a local tavern girl, Willow (Britt Ekland).

Yet a scene for Howie—from the next room—hot and bothered by Willow’s invitation, but unable to join per his religion (he has a fiancée and must wait until marriage) was a bit odd for his character that otherwise condemns and damns their ‘sacrilegious’ customs. Most times Howie appears indignant at their way of life, but on some occasions it comes across as just preachy or comical. He seems more interested in judging them for being pagan than investigating the girl’s disappearance, and when he hurls at the village’s leader, Lord Summerisle (an unrecognizable Christopher Lee) “but what of the truth of Jesus!” I couldn’t help but laugh.

Where “The Wicker Man” suffers is in this battle between Christianity and paganism, and Hardy’s assumption that the bizarre acts perpetrated by the island’s natives would answer for the film’s horror. Of course, the film is based on a novel by David Pinner called “Ritual,” so it’s up for debate if that fault is in fact Hardy’s or the source material.

Odd but Not Unsettling

However, I couldn’t help but notice moments that could have conjured up an eerie sentiment—such as an empty picture on the wall of the tavern, an empty seat in a classroom, and Rowan’s name in a class register—had they been filmed with seriousness instead of camp. The film’s cinematographer Harry Waxman instead shoots quaint scenes of farmland and oceans, or focuses objectively on bizarre aspects like inserting a toad into a girl’s mouth to ‘cure’ her sore throat, while leaving them devoid of horror. Whether this is a cinematic misstep or just a sign of the times is up for debate. It feels very much in the vein of the filming style of “Dirty Harry” (1971) or “Dog Day Afternoon” (1975) in its approach.

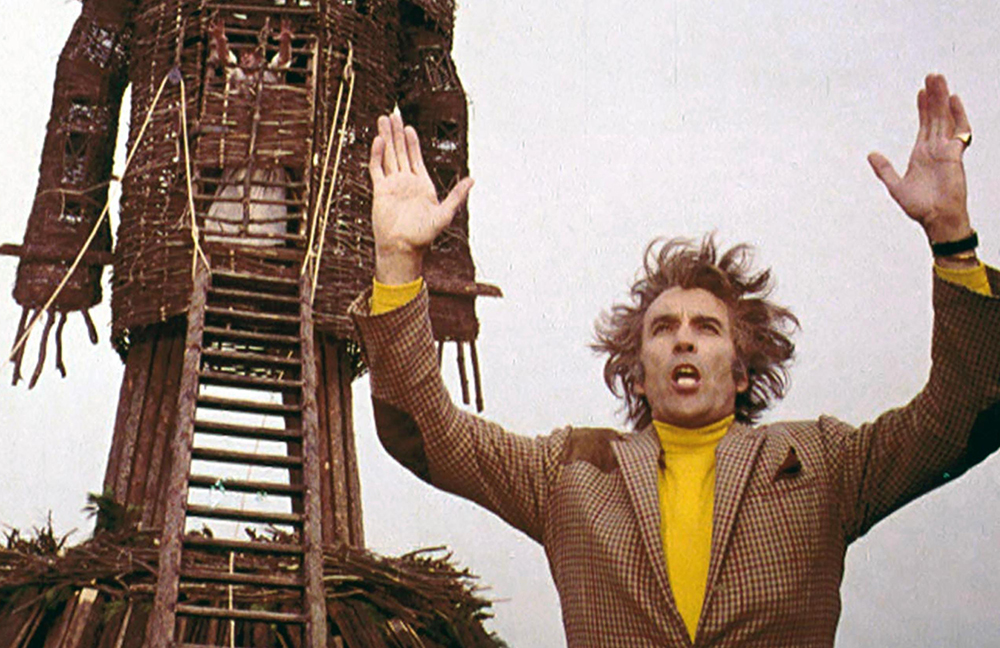

“The Wicker Man” also suffers from a case of too much telling instead of showing, with its ending exposition by Summersisle and townsfolk much like a Bond villain detailing his plan to 007. But, in fairness, the end of the film does have a twist I honestly didn’t see coming, and when the pieces click it adds a layer of macabre to an otherwise bizarre film. As does the film’s penultimate discovery—an immense shot of the nightmarish Wicker Man, shown to us in concert with Howie—which invokes a sense of horror that had been missing up unto that point. The conclusion is interesting, and I don’t want to spoil it here. But suffice to say it flips some now-hackneyed sacrificial scripts on their head, which adds to the film’s credit.

Worth Watching for its Vintage-Folk Feel

In fairness, “The Wicker Man” is not a bad movie. It’s also not purposefully camp, just constrained by the techniques of the time and likely its scant budget ($810,000 with a return of only $148,882). Christopher Lee is a delight to watch, and the actors who play the town’s denizens do act appropriately creepy at times. And Woodard does his best with not much to work with aside from preachy protestations and judgements of the town’s ‘immorality.’

I can imagine hyper-devout Christians experiencing shock at the film’s happenings, but not so much with connoisseurs of horror (see anything “Saw” related and this film becomes not much more than odd). However, the film has gained a cult following and a 7.8/10 rating on IMDb, and is worth the watch for a glimpse of vintage British folk horror. And as Christopher Lee said that Lord Summersisle was “the best part” he’s ever had, it might be worth watching for that alone.

“The Wicker Man” is available to rent via streaming.