There was a time when it felt like the industry was stuck in a loop. Love teams, slapstick comedies, and melodramas dominated screens. And while some of those films had their charm, many felt like they were playing it too safe. Recently, however, we’ve seen a shift—one that’s hard to ignore. Filipino filmmakers are exploring new territory, experimenting with form, and diving into stories that feel bolder and more authentic.

Last year, that momentum only grew stronger. The films that stood out to me were as varied as they were compelling. For example, three(!) documentaries made my top 10—a testament to how nonfiction storytelling in the Philippines has found its voice. There’s also a docufiction that combines fact-based storytelling with populating the film with non-actors in lead roles; a musical based on a stage play that bursts with creativity and immediacy; and, of course, a Lav Diaz film. I mean, really, what’s a Filipino year-end list without one? These films weren’t just made to entertain; they were made to challenge, to move, and to show what’s possible when art takes priority.

It wasn’t easy narrowing my favorites down to just 10. So before diving in, here’s a shoutout to a few honorable mentions that deserve recognition:

- “And So It Begins“ (Ramona S. Diaz)

- “Bini Chapter 1: Born to Win” (Jet Leyco)

- “Under a Piaya Moon” (Kurt Soberano)

- “Your Mother’s Son” (Jun Robles Lana)

- “I Am Not Big Bird” (Victor Villanueva)

Now, here are the 10 films that defined 2024 for me and proved, yet again, why Philippine cinema deserves our full attention.

Read More: Philippine Cinema, Front and Center: The Top 10 Filipino Movies of 2023

10. ‘Outside’ (dir. Carlo Ledesma)

Carlo Ledesma’s “Outside” reimagines the zombie apocalypse genre as a tense psychological drama, foregoing blood-soaked thrills for emotional depth. Led by a stellar performance from Sid Lucero, the film delves into themes of paranoia, generational trauma, and fatherhood, using the zombie outbreak as a backdrop rather than the main event.

At its heart is Francis Abel (Lucero), a man haunted by childhood abuse, now fleeing to his late father’s remote estate with his wife Iris (Beauty Gonzalez) and their sons. The supposed sanctuary quickly becomes a crucible for buried tensions, especially when Francis’ estranged brother Diego (James Blanco) arrives. Lucero’s portrayal of Francis—torn between protecting his family and confronting his past—anchors the film’s emotional core, particularly in his fraught relationship with his eldest son, Joshua.

Ledesma skillfully crafts tension through quiet domestic moments, reminiscent of “Take Shelter” and “A Quiet Place.” These interactions reveal that the real danger lies within: unresolved hurts and fears threatening to tear the family apart. While the slow pace and lack of traditional zombie action may disappoint some, “Outside” shines as a meditation on survival, trauma, and the fragility of familial bonds. Though divisive, Ledesma’s film challenges genre conventions, offering a poignant examination of the monsters inside us.

9. ‘Lost Sabungeros’ (dir. Bryan Kristoffer Brazil)

Bryan Kristoffer Brazil’s “Lost Sabungeros” dives into one of the Philippines’ most chilling mysteries: the disappearance of 34 cockfighting enthusiasts between 2021 and 2022. The documentary weaves together the families’ relentless quest for answers with a critique of a justice system that often serves the powerful over the powerless.

Sabong (cockfighting), a cultural tradition, shifted online during the pandemic, turning into the dangerous world of e-sabong. Against this backdrop, Brazil recounts the harrowing stories of the missing sabungeros and their families, such as John Claude Inonog, Ricardo “Jon Jon” Lasco, and Edgar Malaca. Through raw interviews and archival footage, the film captures their pain and exposes systemic impunity. A mother’s poignant question—“Is justice really only for the rich?”—echoes throughout, reinforcing the documentary’s central theme of unchecked power.

Despite melodramatic moments, TV-quality execution, and uneven pacing, “Lost Sabungeros” remains impactful. Its eleventh-hour cancellation from last year’s Cinemalaya due to “security concerns” underscores the risks Brazil and his team took to tell this story. Later screened at QCinema, the film refuses to let these disappearances fade into obscurity. While it doesn’t solve the case, it ensures the missing sabungeros—and their families’ fight—are not forgotten.

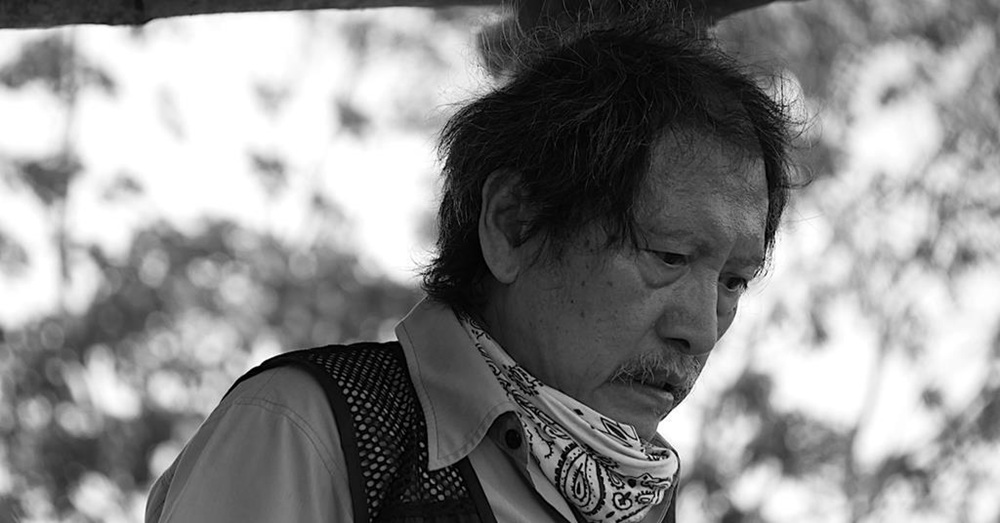

8. ‘The Gospel of the Beast’ (dir. Sheron Dayoc)

“The Gospel of the Beast,” directed by Sheron Dayoc, is a lurid, violent coming-of-age crime thriller set in the harsh realities of the country. The film follows 15-year-old Mateo (Jansen Magpusao), who navigates a tumultuous life marked by poverty and violence. After a traumatic incident involving someone from school, Mateo seeks refuge with Uncle Berto (Ronnie Lazaro), a leader in a gang of thieves and a confidant of the former’s erstwhile-missing father. As Mateo becomes entrenched in this criminal world, the film zeroes in on how gangs can serve as surrogate families for troubled youth, providing a sense of belonging amidst desperation.

As a pioneer of the regional cinema movement in the Philippines, Dayoc presents a gritty yet realistic portrayal of the influences shaping Mateo’s morality, highlighting the inevitability of his transformation into a hardened criminal in a society where violence is ubiquitous. The cinematography by Rommel Andreo Sales imparts a dreamlike quality to the stark settings, juxtaposing beauty and despair.

With the film’s heavy themes, any sliver of hope feels absent, leaving viewers to grapple with the harsh realities of Mateo’s world. The performances, particularly those of Magpusao and Lazaro, are topnotch, capturing the tragic acceptance of a life devoid of hope. Ultimately, “The Gospel of the Beast” delivers a grim but powerful narrative about survival in an unjust world.

7. ‘Alipato at Muog’ (dir. JL Burgos)

Films that confront human rights violations perpetrated by the state are essential viewing. For one, they ignite public consciousness and stir action, effectively shaking people out of their sociopolitical apathy. JL Burgos‘s “Alipato at Muog” (lit. ‘Flying Embers and a Fortress’) powerfully addresses the enforced disappearance of his brother, Jonas Burgos, in 2007.

For years, tens of thousands of brave individuals fighting for human rights and defending marginalized communities have been abducted, often disappearing without a trace. “Alipato at Muog” focuses intently on one man’s disappearance and his family’s relentless quest for the truth, making it undeniably clear that the case of Jonas must never become a reality for anyone else. Sadly, given the harsh realities we face, this much-needed change is unlikely to happen in our lifetime.

While the film has some cinematic shortcomings—particularly the inclusion of animated sequences—these issues are minor compared to its impact. As a facts-based narrative, “Alipato at Muog” stands out as a gripping documentary that deserves recognition as one of the finest films in Philippine cinema this year.

6. ‘Green Bones’ (dir. Zig Dulay)

In “Green Bones,” director Zig Dulay once again delves into the heart of rural life, weaving together drama, police procedural, and social commentary into a tapestry that feels both nostalgic and deeply unsettling. Dulay’s fascination with uncovering the fragmented pasts of his characters is on full display, drawing viewers into a world where moral certainties are anything but assured. Co-written by Ricky Lee and Anj Atienza, the screenplay uses introspective voiceovers and epistolary confessions to anchor its narrative. While these devices lend emotional weight, they also risk overloading the story with exposition, leaving some thematic threads underexplored.

At its core, however, “Green Bones” thrives on its performances. Ruru Madrid delivers a relatable turn as a young corrections officer whose unwavering sense of justice blinds him to the complexities of truth. But it’s Dennis Trillo who steals the spotlight. As a prisoner accused of an unspeakable crime, Trillo offers a masterclass in restraint and depth, compelling audiences to confront their own biases about guilt and redemption. His portrayal humanizes the dehumanized, blurring the lines between victim and villain in a justice system rife with corruption.

While the film falters as a pointed critique of institutional failings, it soars as a character-driven drama. Dulay’s ability to find beauty and hope in the bleakest of circumstances is undeniable, and the film’s final moments resonate with a quiet optimism and hope. “Green Bones” may not rewrite the rules of the genre, but it reaffirms Dulay’s talent for crafting narratives that challenge and inspire in equal measure.

5. ‘Phantosmia’ (dir. Lav Diaz)

Lav Diaz, the unparalleled maestro of Philippine slow cinema, delivers one of 2024’s most profound films with “Phantosmia.” This 4-hour black-and-white epic melds the psychological, political, and the poetic into an agonizing exploration of trauma, violence, and redemption.

The story follows Hilarion Zabala (yet another solid performance from Ronnie Lazaro), a retired scout ranger haunted by phantosmia—phantom smells linked to repressed memories of wartime atrocities. Assigned to Pulo Penal Colony, he must confront not only the ghosts of his military past but also the island’s grotesque present, embodied by figures like the corrupt Major Lukas (Paul Jake Paule) and the exploitative Narda (Hazel Orencio). Amidst the chaos, Zabala’s journey intertwines with Reyna (Janine Gutierrez), a young woman sold into abuse, and the eccentric poet Marlo (Dong Abay), whose whimsical verses offer moments of levity in an otherwise brutal narrative.

Diaz’s signature aesthetics—unhurried pacing, unflinching realism, and natural soundscapes—are tempered here with a newfound contiguity. Themes of systemic violence and moral awakening resonate powerfully, as Diaz crafts one of his most accessible yet politically charged works. “Phantosmia” reaffirms Diaz as a revolutionary voice in global cinema, delivering a cinematic experience both deeply human and indelible.

4. ‘Ghosts of Kalantiaw’ (dir. Chuck Escasa)

In just over an hour, Chuck Escasa’s “Ghosts of Kalantiaw” dissects the fragile boundary between historical truth and cultural mythology, delivering one of the most thought-provoking Philippine films of 2024. At its core is the legend of Datu Kalantiaw, a figure revered in Batan, Aklan, whose supposed Code of Kalantiaw has long been debunked as a hoax yet remains woven into the town’s identity. Juxtaposing this pseudohistory with the post-truth era embodied by figures like current President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr., Escasa’s documentary interrogates how myths and falsehoods are upheld, even by those who denounce similar distortions in other contexts.

The documentary’s power lies in its ability to reveal people’s intrinsic inclination to selectively embrace truth. It shows how cultural pride and deeply ingrained traditions resist factual evidence, creating cognitive dissonance for the film’s subjects and its viewers alike. With understated but incisive storytelling, Escasa avoids sensationalism, opting instead for a reflective tone that, with the help of historians like Ambeth Ocampo, probes the consequences of historical fabrication.

Through expert interviews and searing commentary, “Ghosts of Kalantiaw” examines the political exploitation of history and the resilience of myths as tools of power. More than a documentary, it’s among the best Philippine cinema has to offer. It masterfully explores identity, memory, and the enduring battle for truth in a world awash with misinformation.

3. ‘Kono Basho’ (dir. Jaime Pacena II)

In “Kono Basho,” Ella (Gabby Padilla) travels to Rikuzentakata, Japan, to attend her estranged father’s funeral. There, she meets her half-sister Reina (Arisa Nakano) and confronts the emotional complexities of their shared loss. As Ella grapples with her bitterness towards their father, she sees Reina as a reminder of the life he chose. Conversely, Reina, who longed for their father’s approval, views Ella as the sister she has always aspired to be.

Set against the backdrop of Rikuzentakata’s recovery from the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, the film delicately charts the divergent paths of the two sisters as they process their grief. Director Jaime Pacena II, making his directorial debut, showcases a remarkable confidence, enhanced by Dan Villegas‘ cinematography and Len Calvo’s lush piano-centric score. The film harmonizes the melodramatic elements of Philippine cinema with the subtle beauty of Japanese storytelling.

Despite its occasional overuse of poeticism to convey themes of rebirth and moving forward, “Kono Basho” offers an intimate examination of loss and identity. In its poetic meditations, it highlights the intersection of Japanese and Filipino cultures, united by similar values. Ultimately, Pacena and his team deliver a poignant message: moving forward doesn’t necessarily mean letting go, but rather integrating loss into one’s existence.

2. ‘Isang Himala’ (dir. Pepe Diokno)

There’s a scene in “Isang Himala” (lit. ‘A Miracle’) where Elsa, portrayed by Aicelle Santos, cries out to the heavens: “Madaya ka! Ako’y kausapin mo!” (“You are so unfair! Talk to me!”). This raw, emotional moment encapsulates the essence of Pepe Diokno’s adaptation of Ishmael Bernal’s 1982 classic, “Himala.”

Instead of attempting to equal Nora Aunor’s timeless performance, Santos reinvents Elsa for a new generation, balancing defiance and vulnerability to create a portrayal that is both fresh and deeply resonant. Her interpretation anchors the film’s introspection of faith, doubt, and the insatiable search for meaning.

Naturally, music plays a central role in this musical adaptation, with Vincent de Jesus’ compositions and Ricky Lee’s lyrics adding depth to the narrative. Santos’ anguished monologue-turned-song is a standout, embodying the emotional and spiritual turmoil of Cupang’s residents. However, it’s Kakki Teodoro’s portrayal of Elsa’s worldly and fiercely loyal friend Nimia that stands out. Without question, her turn as Nimia ranks among the top acting moments in Philippine cinema this year.

The film’s abstract, stage-inspired visuals may divide viewers, sure. Nonetheless, they amplify the story’s allegorical weight, focusing attention on the characters’ inner struggles. By blending the intimacy of theater with the grandeur of cinema, Diokno directs a film that feels timeless yet urgent. Ultimately, “Isang Himala” is not just a retelling. Instead, it’s a renewal, one that preserves the original’s core themes while offering a poignant reflection on belief and the human condition.

1. ‘Tumandok’ (dirs. Richard Jeroui Salvadico, Arlie Sweet Sumagaysay)

I must confess: Before viewing “Tumandok” (lit. ‘The Inhabitants’), I thought it would be Cinemalaya’s version of “Killers of the Flower Moon.” However, that comparison, though flattering, diminishes the film’s unique power.

Directed by Richard Jeroui Salvadico and Arlie Sweet Sumagaysay, “Tumandok” profoundly captures the essence of indigenous life, set against the stark indifference of local government. Casting actual tribespeople for the principal roles, it becomes a melding of narrative fiction and the urgency of documentary filmmaking. Though a fictional story, the fact that the filmmakers cast them makes it a seamless exercise. Their presence alone gives audiences access to the tribe’s way of living, along with the challenges they face daily.

One line in particular lingers in my mind: the Chieftain’s heartbreaking plea to an official—“Tell us where the end of the earth is, and we will go there to live in peace.” With a compelling screenplay by Sumagaysay and Arden Rod Condez along with stunning cinematography by Pabelle Manikan, the film resonates deeply; especially when the music—a collaboration between musician Paulo Almaden and the Ati people—plays during pivotal moments, like when En (Jenaica Sangher) expresses her dreams for her tribe. I found myself in tears and filled with hope.

“Tumandok” boldly confronts issues like land-grabbing and extrajudicial killings disguised as military operations. The Ati tribe’s story reflects the struggles of many other indigenous peoples in the archipelago, who face daily injustices that often go unheard. As the best film of Philippine cinema in 2024, this docufiction serves as a powerful call to action against these social issues.