For a certain generation of Filipinos, the Eraserheads were more than just a band; they were a cultural shift. If being billed “The Beatles of the Philippines” feels like an overstatement, it’s only because no label can quite capture the way their music embedded itself in the national consciousness. They had the scrappy irreverence of The Ramones, but their storytelling—simple, sharp, and deeply attuned to everyday life—made them anthemic.

Maria Diane Ventura’s “Eraserheads: Combo on the Run” understands this completely. The documentary, packed with interviews from the band, music historians, and industry insiders, takes a straightforward talking-heads approach, but what it lacks in visual flair, it makes up for in emotional weight. The ‘Heads have never been the type to mince words, and here, they finally say what fans have speculated about for decades.

The Weight of History

The film wastes no time explaining why the Eraserheads mattered. Within minutes, it situates their rise against the backdrop of the late ‘80s and early ‘90s—a post-EDSA era of democracy, freedom of expression, and, crucially, a hunger for something fresh. Their frontman and primary songwriter, Ely Buendia, had a knack for crafting deceptively simple lyrics that captured the spirit of the times, whether through the wistful nostalgia of “Minsan” or the quiet reassurance of “With A Smile.”

The band’s origin story is classic rock mythology: Buendia, a student at UP Diliman, put up a dorm-room ad looking for new bandmates after his previous group fell apart. Three fellow UP students answered—bassist Buddy Zabala, who anchored their sound with steady, unfussy playing; drummer Raimund Marasigan, who brought an experimental edge that would push the band beyond simple pop-rock; and guitarist Marcus Adoro, whose raw, almost unpolished style added a scrappy charm. At first, even Buendia himself wasn’t impressed. But something clicked, and soon, this unlikely group found themselves at the forefront of a new movement in Filipino music.

Archival footage of their early days is one of the film’s highlights, capturing the energy of a band that, despite its internal fractures, seemed destined for something big. Their ascent—getting discovered at a university gig, cutting an album that would go on to define a generation—plays out like a fairy tale, except, of course, fairy tales don’t usually end in acrimonious breakups.

Reckoning with the Past

If nostalgia is the hook, then the real meat of the documentary involves its honesty about the band’s complicated relationships. The Eraserheads were never the kind of band that projected brotherhood and camaraderie. They were always a little distant with each other, and the years of speculation about in-fighting weren’t just fan theories.

Ventura, who was married to Buendia during the peak of the band’s tensions, knows exactly which wounds to press. Each member gets a chance to explain their version of events: Buendia’s growing frustration with the trappings of fame infringing upon his personal life, Marasigan’s struggle to keep the band together, Zabala’s disappointment with Adoro’s often erratic playing. The resentment built up over years of unspoken grievances, even more amplified by the fact that—as Buendia and Zabala make clear more than once in the film—the guys grew up in a time when men didn’t normally talk about what they really felt.

[Related Review: ‘Who By Fire’: Philippe Lesage’s Slow-Burn Examination of Fractured Egos]

When Music Brings People for Healing

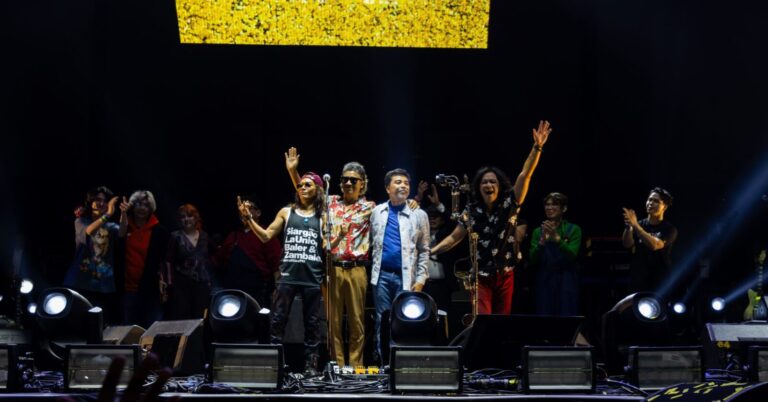

The documentary also frames their 2022 “Huling El Bimbo” reunion concert as not just a comeback, but an act of healing for several reasons: for a country still reeling from a still-ongoing pandemic, a politically divided nation, and most importantly, for the band itself.

Interestingly, this reunion was preceded by a viral Twitter exchange in 2021, where a fan asked Buendia if an Eraserheads reunion was possible. His half-serious reply: “Pag tumakbo si Leni” (“If Leni runs”). Days later, then-Vice President Leni Robredo announced her presidential bid. While Buendia later clarified that he replied to the post in jest, the timing added a layer of political symbolism to the band’s eventual return.

The documentary subtly weaves this narrative, highlighting how the Eraserheads’ music continues to resonate amidst the country’s socio-political landscape. Marasigan puts it best: “Seeing the band is like [seeing]your ex-girlfriend—you’re just happy you don’t hate each other.” It’s a stark but accurate summation of where they stand now.

The Adoro Problem

And then there’s Marcus Adoro.

The film does not ignore the elephant in the room, addressing his documented history of abuse allegations. But the way the film handles it feels…uneasy. The documentary presents his side of the story, with Adoro claiming to have sought help, but his victims’ voices are notably absent. It’s an omission that sticks out, especially in a film so committed to truth-telling.

And this is where ‘Combo on the Run’ raises an interesting question: What makes a great documentary? Is it one that presents every angle, no matter how uncomfortable, or is it one that sticks to a specific perspective, in this case, the band’s? The film is refreshingly candid about the internal conflicts of the Eraserheads, but when it comes to Adoro’s controversy, it hesitates. Unlike the band’s long-standing creative and personal disputes—which Ventura gives ample space to breathe—the documentary handles Adoro’s issue briefly. Then, it completely brushes it aside, as if closure has already been reached.

That gap in storytelling undermines what is otherwise a deeply introspective film. The documentary is about reconciliation, but for whom? If the Eraserheads are finding peace with each other, that’s one thing. But when one of them has unresolved allegations that go beyond mere band tensions, the idea of “closure” feels incomplete. The film’s biggest strength is its honesty, but it falters when that honesty becomes inconvenient.

The Eraserheads’ Final Chord

For all its flaws, “Eraserheads: Combo on the Run” succeeds in what it sets out to do: it gives the Eraserheads the space to tell their story, on their own terms. It’s not an investigative deep dive, nor does it try to be. Instead, it’s a confessional—sometimes funny, sometimes painful, but ultimately honest.

And then there’s the moment that stays with me. Near the end of the film, a montage plays: the four of them bonding over dinner, singing with family and friends in a karaoke bar, on the road together for their world tour—all visibly at ease, with none of the tension that defined their earlier years. Over this, their song “Balikbayan Box” plays, with Buendia’s voice repeating, “Umuwi na tayo, hey hey hey” (“Let’s go home, hey hey hey”). It’s a simple refrain, but in this context, it cuts deep. After everything—decades of friction, breakups, reconciliations—you can’t help but wonder: Do they finally see each other as home?

Personally, I’d like to think so.

As the film closes, Buendia—who once famously declared that they were never really friends—offers a quiet retraction: “We were never not friends. We just had a falling out.” It’s not exactly a grand reconciliation, but it’s something.

Take that, Glenn Frey.

Maria Diane Ventura’s “Eraserheads: Combo on the Run” served as the opening film at the second Manila International Film Festival (MIFF) last March 4, 2025. The film will have a limited release in select theaters across the Philippines from March 21 to 23, 2025. Follow us for more coverage.