Man, this movie gets a bad rap. 15% Tomatometer score on the aggregate site Rotten Tomatoes, with an equally abhorrent 43% user score on the same platform. Horror aficionados follow suit, and rather than story deficits, I think their umbrage has more to do with seeing anyone other than anointed one Robert Englund don the facial burns and finger knives. Fred Krueger went from a mostly silent dream demon in the excellent series opener, to varying degrees of stand-up comic in every entry after the controversial Part 2. What the series lost after that 1985 film was the idea of what Krueger was. He wasn’t an undying or undead brute like Michael Myers or Jason Voorhees. He wasn’t a cautionary tale against teen sex. He wasn’t a “fun” horror baddie. He was a burned-alive, come-back-to-stalk-you-in-your-dreams demon. He was a child murderer. And, what filmgoers and filmmakers alike shy away from admitting—he was a likely pedophile.

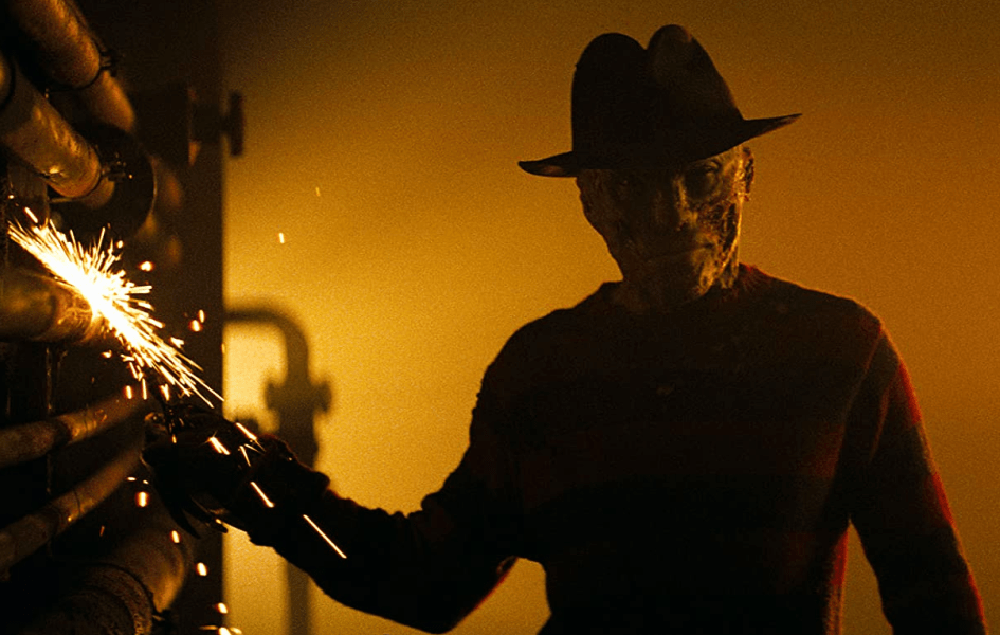

Samuel Bayer’s 2010 remake starts in a vicious manner, setting up that this will be a disturbing film, not a comical one. A teenager named Dean (“Twilight’s” Kellan Lutz), plunges a knife into his own throat and slits it open in front of one of his friends. Of course, it’s not suicide, but a dream-murder fostered by Fred Krueger. The cinematography is serious from the word go. Reds and blacks intertwine with rusty metals and slick-sounding scraping effects to paint the dream world in desolate bleakness.

“A Nightmare on Elm Street” is a remake in the truest sense of the word. It stars several touted talent for the decade, most notably Rooney Mara, and makes the wise decision to not layer the film with needless homages, either in terms of past actors or sequences. There’s a couple violations, such as Krueger coming through the walls to stalk Nancy (Mara) in her dreams that is a CGI upgrade from the original film, as well as a body bag being dragged through the high school halls that is a straight “homage” copy.

But shot-for-shot, this film is desolate and mean-spirited—and that’s a compliment. Somewhere along the way, “A Nightmare on Elm Street” and Freddy Krueger became cannon, collectibles alongside Jason Voorhees, Michael Myers, Pinhead, Chucky, etc. But what’s collectible about a serial child murderer, who was likely that and much worse? Screenwriters Wesley Strick and Eric Heisserer understand there’s nothing slapstick about Krueger. What one-liners he does utter are sardonic and fear-inspiring. They permeate through the nightmare-inducing landscape like screams in an echo chamber.

We should talk about Jackie Earle Haley, who plays Krueger. In a Vanity Fair interview Haley speaks of following director Bayer’s advice to go back to Freddy’s roots, when he was actually scary. Haley is Krueger re-imagined. He’s cast in darkness just like Englund was in the original. He talks more than in the original film, but it’s purposive. The “one, two, Freddy’s coming for you” line is repurposed with the demon’s taunting and stalking modus operandi. Jump roping girls make a slight appearance, but overall Bayer and company take Krueger’s victims back to an elementary school where something horrible happened, something elaborated on only by sinister dream sequences and the horrified look on Nancy’s friend Quentin’s (Kyle Gallner) face as he flips through unspeakable photographs he’s found of Nancy as a child in Krueger’s lair.

Prior to this, Bayer does something interesting—he offers the audience a red herring, offering a conclusion that Krueger may indeed have been innocent. Its revelation in the film’s final act is unspeakable, and as innocence-shattering as they come. The proceedings are helped by Mara and Gallner, who are both wonderful actors here, as well as Haley, who is not jokester, but nothing short of a vicious, sadistic murderer.

Some problems present themselves, most notably some parental figures (Connie Britton, Clancy Brown), who are mostly absent, and tell one form of lie after another to hide the secret of their children’s abuse at the hands of Krueger from them. Also, the truth of what happens to Krueger is truncated, told in half truths at both the parents’ hands and Krueger’s as he manipulates hideous dreams.

The GCI is often too big and bold; the limited special effects of the original made it more spooky and harrowing; but here the gore is increased—to its benefit. Unlike the torture porn that littered the decade, “A Nightmare On Elm Street” uses it for necessity. Krueger’s psychological and physical torture of characters drives his evil; his murders are violent and quick. And, in one of the film’s best sequences, as he stalks Nancy through a pharmacy, the latter slipping in and out of micronap delirium, the special effects and juxtaposition of dream and reality create one of the most intensely visual experiences of the film. “A Nightmare on Elm Street” also takes pains to show the psychological trauma of insomnia and sleep deprivation in a way explored in the original, but abandoned altogether for all subsequent films.

Some closing elements (Nancy uttering a cringe-worthy line from “Freddy vs. Jason” and an ending sequence that is predictable and insulting) lower the impact of the film overall, regrettably. If nothing else, “A Nightmare on Elm Street” is a fitting remake, one that hinges on the pure evil that Krueger simply is. Wes Craven originally wanted Krueger to be a one-and-done. He also re-edited his original script to exclude Krueger’s clear pedophilia. This remake may not be a perfect film; but it’s dark, evil, and unapologetic. If nothing else, I credit Bayer for having the guts to lay bare what Krueger was once and for all—and his critical lashing shows he may have just touched the right nerve after all.