After the release of “Julieta” in 2016, director Pedro Almodóvar described his process working with actors: “I battled a lot with the actresses’ tears, against the physical need to cry,” he said. “It is a very expressive battle…I didn’t want tears, what I wanted was dejection.” About halfway into “Pain and Glory,” the sentiment is raised again when Antonio Banderas’ character Salvador Mallo proclaims that great actors do not cry, they try to hold their tears in as much as they can. This point of view is not something new, of course. Michael Caine echoed a similar statement several years ago during a masterclass on acting.

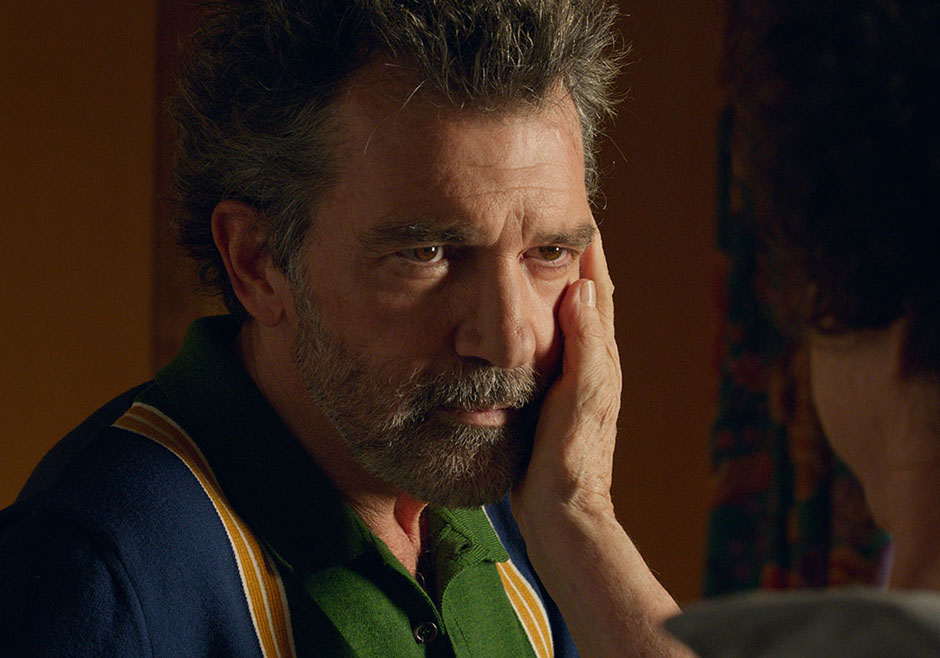

It isn’t surprising then that Banderas listened to his director’s advice and true-to-form, restrained from crying. Yet, there’s something about his eyes that remain utterly captivating as his character goes through a range of different emotions. The extent to which he seems able to externalise deep-seated feelings of regret, pain, and nostalgic yearning with such subtlety is a testament to the kind of actor he is. As well as his working relationship with Almodóvar. There are many heartbreaking moments throughout this film, and we never see Mallo break down; but watching his pain certainly brings the tears flowing for the audience—well at least for me anyway. Crying is something I expect to be doing whilst watching a Almodóvar film. The Spanish master of melodrama retains the majority of the many themes he’s known for in his 21st outing. This self-reflective, somewhat autobiographical ode to the passage of time is a tender and modest drama in which Mallo, a celebrated and ageing filmmaker in the middle of a creative crisis meanders between memory and loss.

Gravely depressed and suffering from a number of different ailments, he re-evalutes “Sabor,” a newly restored film of his which is celebrating it’s 30th anniversary. Before long, he’s reunited with two people he did not expect to see, including the lead in said film Alberto Crespo. (Asier Etxeandia). Their meeting leads Salvador to see the film, himself as well as the past in a new light. He treads into his mind and visits poignant memories from his childhood including time spent with his mother (Penelope Cruz). The reflections throughout give the impression that maybe this is Almodóvar’s “8½;” but that would be an injustice to both Fellini and the Spaniard. “Pain and Glory is a much more personal story, even for someone who’s dedicated their filmic life to the inclusion of auto-fiction. It almost feels like a therapy session from the director to himself as he explores Mallos’ (or his) first sexual awakening, first love, as well more meditative contemplations on work, and what it means to be a filmmaker.

Perhaps what separates this from a ‘typical’ Almodóvar film is the restraint the director shows. We are used to watertight screenplays from the Spaniard and we get that again here. However, the film refrains from the usual dramatic extremes that he’s given us over the last four decades. He’s known for his stories-within-stories, metafiction elements, and a penchant for big reveals at the end to tie it all together. When I think of his filmography, I think of films like “The Skin I Live In,” “All About My Mother,” and “Bad Education.”

These stories know how to use complex, sometimes non-chronological meta structures. He tends to leave room at the end for us to breathe, a catharsis of sorts. “Pain and Glory” doesn’t do this, instead, the film drip feeds the information needed to understand the characters behaviour throughout without offering any real reward for having spent time with them. This slice of life narrative style might be frustrating to those not used to a slower pace. It’s a story largely told on emotional terms, and it’s told through the performance of our lead. When the end comes, it’s as bittersweet as ever.

In terms of filmmaking, Almodóvar is at his peak powers. His eyes for colour remain and it seems he’s grown more mature than ever. Like John Cassavettes before him, he’s an actor’s director and is wonderful at getting the best out of his on-screen talent even with smaller roles. His muse Cruz remains excellent along with Asier Etxeandia, Leonardo Sbaraglia, and Julieta Serrano also manage to get the most out of their limited screen time. The filmmaker has always had the ability to craft a visual story whilst finding angles that completely alter what we’re seeing from the mundane to larger than life moments. With “Pain and Glory,” he adds something more.

Within the film, pivotal events from childhood are confronted and juxtaposed with the present—which is full of pain and creative block. The plot of the film moves forward via Mallo’s attempts to continue with his craft. His depression and isolated present is progressively illuminated through his art, a symbol that is confirmed in the apotheosis of the final scene. It is through his art, the film “Sabor” that he is reunited with his past. The exercise of empathy that the craft of writing and filmmaking demands is what allows him to reconcile himself and pay off the pending debts with the people that marked his life: his mother, his colleagues, his ex-lover and, finally, with the person he was, with the child that was to become the film director that delivers to us this brilliant self-portrait. In turn, we are invited to look at this film as the mirror it is. The seamless interweaving of past and present and Mallo’s navigation of them compels you to appreciate your own existence. There are very few movies that are able to do that. This is Almodóvar at his best, delivering to us yet another masterpiece.