In 2009, “Saturday Night Live” aired a sketch that touched upon tourism in Hawaii. In it, guest host Dwayne Johnson and cast member Fred Armisen played Hawaiian natives working in a restaurant that tourists frequented. The duo sang and danced their way from table to table, giving the patrons a dose of reality check about what was happening behind the scenes on the island. The description of the sketch? The island has many volcanoes ready to erupt.

On surface, especially for the uneducated, it might have served only as a sketch. But for the local residents who know, the sentiments were painfully accurate.

I was reminded of that SNL sketch upon watching “Cane Fire,” Anthony Banua-Simon’s debut documentary feature. The film critically examines the economic and cultural pillaging of Hawaii that dates back over 200 years, and how such exploitation infuriatingly continues to this day. At the same time, the documentary feature serves as the director’s personal love letter to four generations of his family who have called the island, not a dream destination, but their home.

Equal parts experimental, incisive, critical, and emotional, “Cane Fire” is his earnest attempt to correct the perception of Hawaiian identity that continues to be perpetrated by popular culture.

A Well-Researched Documentary About Hawaii’s History

Banua-Simon tells his story using an interesting, if at times dizzying, approach. Here, he contrasts the palpable fakery of amateur travelogs and Hollywood song-and-dance sequences with his own video footage of his great-uncle and cousins, as well as acquaintances he met along the way. Consequently, “Cane Fire” succeeds in juxtaposing the illusion and the reality.

Before all these, however, was the island’s history; from the Kingdom of Hawaii’s forceful overthrow with the help of the U.S. Navy, to the rise of the ‘Big 5’ U.S. companies that own most of the island to this day. These ‘Big 5’ companies began as sugar and pineapple plantations, profitable ventures that controlled Hawaii’s economy. With industry growth came the need for manpower, so the companies sourced from all over the world for workers. From China and Japan to the Philippines, laborers flocked to Kauai for the opportunity.

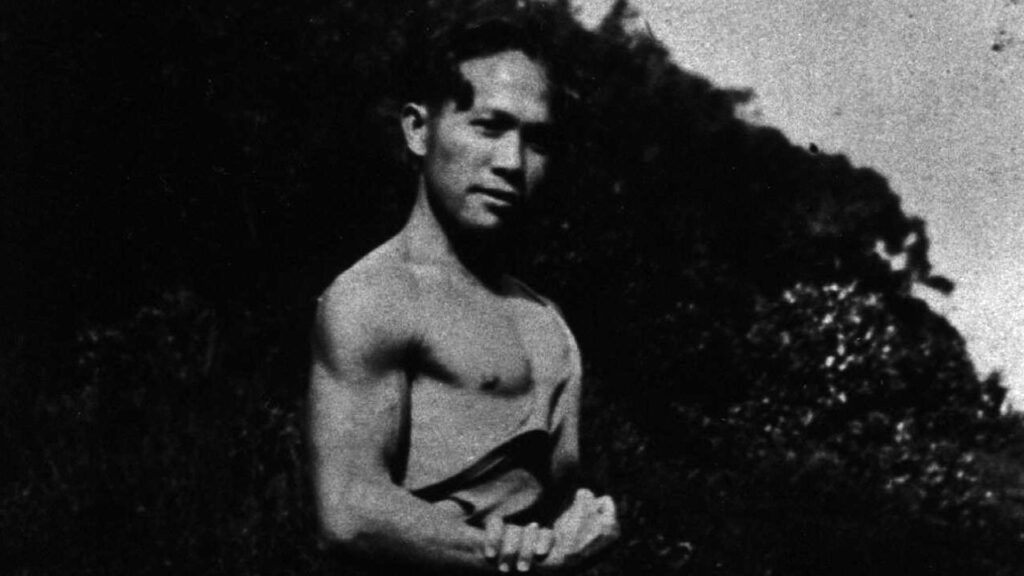

This is where it gets personal for Banua-Simon: his great-grandfather, Albert, migrated from the Philippines for such work. Workers would live in camps within the plantations, each ethnically segregated (Filipinos, Japanese, Chinese, Koreans, Whites, and Europeans). As the terrible working conditions worsened, the owners would quash any attempts at unionization by pitting the ethnic groups against each other. Albert himself decided to become a union member; something that didn’t sit well with the owners, who demoted him from supervisor to ditch digger.

Eventually, the appalling labor conditions reached the world stage, affecting the reputation of the industry. As damage control, the ‘Big 5’ launched a campaign to market their labor practices as worker-friendly. With the help of major Hollywood studios, tourists were lured to the island through cruise ships. This started the subsequent transition from sugarcane plantation to a new dominant industry throughout the island: tourism.

Hollywood’s Role in Creating the ‘Escapist Fantasy’

“Cane Fire” opens with a title card; “Over the last century, more than a hundred feature films have been shot on the Hawaiian island of Kauai,” it reads. It shows snippets of some of these films, where the characters treat Kauai as an exotic and uncharted tropical paradise. Indeed, movies set in Kauai are aplenty; from films starring Elvis Presley and John Wayne to Kevin Costner and Nicolas Cage.

Nonetheless, among the earliest films shot in Kauai, Banua-Simon focuses his attention on a lost film: Lois Weber’s “White Heat,” also known as Cane Fire. Released in 1933, the movie was about a Native worker falling in love with the owner. The film’s ending, which sees the worker burning down the plantation, courted controversy; the regulators deemed it ‘indecent,’ ‘immoral,’ and one that would ‘tend to incite to crime.’ And since it came at a time when the sugar and pineapple industry dominated the island, the ratings board feared it might encourage labor revolt.

Hollywood, for its part, took advantage of the beach fronts for their ‘South Seas Fantasies.’ It didn’t matter if they couldn’t tell the difference between Native Hawaiians from Asian immigrants. After all, studios only needed to cast extras to populate the movies; so whether they interchanged Hawaiians and Asians wasn’t a big deal for them.

These local residents ended up filling the part for extras, and not the lead roles. And instead of opportunities for locals to be stars in movies shot in their own land, these ventures left a bitter aftertaste. Of the locals’ role, a friend of Banua-Simon’s great-uncle puts it simply, “[The] walking background kind, you know?”

Something noteworthy: Banua-Simon’s great-grandfather Albert was also used as an extra while on the job.

The film? Weber’s “White Heat.”

An Island at a Breaking Point

Ask a random person about Hawaii, and the first thing that comes to their mind would most likely be paradise and the escapism it provides. It might be understandable, given that tourism serves as the island’s main source of revenue.

“Cane Fire,” however, takes the audiences behind the scenes—past the illusion, and back to the island’s history. From the colonization of the United States to the introduction of sugarcane and pineapple plantations to the island, Banua-Simon refers to the current situation of Kauai as an island “at a breaking point.”

Through the eyes of Banua-Simon’s great-uncle Henry, “Cane Fire” provides valuable insights about the stark change in Kauai. They visit sugar mills and pineapple canneries, now abandoned and decommissioned, where Henry used to work as a truck driver. The decline in sugarcane and pineapple plantation meant that workers brought to Kauai now had no jobs to turn to. Some had to go back to square one working in the service industry just to survive; others had no other recourse but to go back to their countries of origin.

By contrast, as Hollywood’s fascination with the island receded, the wealthy residents began to take center stage. Movie stars such as Pierce Brosnan acknowledge that while Kauai is a paradise, it’s not for everyone and that it’s somewhat an illusion. On the other hand, you have Mark Zuckerberg’s 357-acre beachfront property; something that follows a long list of hundred-and thousand-acres of private clubs and beachfront properties owned by wealthy residents and investors.

Of Dreams of Owning Houses

As Kauai’s industry slowly transitioned from industrial agriculture to tourism, the ‘Big 5’ also kept abreast of the change, diversifying their businesses to keep up with the times. This, in turn, allowed them to maintain a strong grip on the island’s economy and resources. Nonetheless, this shift meant that the cost of living also went up. This explains why today, the island has the highest cost of living in the entire United States; home listing reports state that Hawaii is the most expensive state for residential real estate in the country.

And as the island continues to fulfill the escapist fantasy, local residents and Native Hawaiians experience the effects, many of whom couldn’t afford to buy houses. Banua-Simon’s interviews with locals (including with his cousins) shed light on the reality behind the façade; it’s devastating to hear them say that owning a property in Kauai is a dream.

While Hawaiian residents struggle to make their dreams a reality, “Cane Fire” reveals the maddening statistics: 50% of the properties in Kauai are owned by non-permanent residents, either as their second homes or investment properties. Banua-Simon then juxtaposes this with a clip from Waimānalo Eviction. It’s a heartbreaking video seeing homeless Native Hawaiians violently evicted by police—when it’s their right to live on the island to begin with.

“Cane Fire”: A Filmmaker’s Personal Ode to His [Extended] Family

When Albert returned to the Philippines, he left his family in Kauai, where many of Banua-Simon’s relatives still live today. Thus, aside from its indictment of the hyper-exploitation to the island, “Cane Fire” is a personal journey for the filmmaker. In his attempts to understand the history of Kauai, he also reconnects with his extended family.

As an outsider (he grew up in Seattle), Banua-Simon brings along an objective perspective to the film. And as he began watching films shot in Hawaii at the same time interviewing his relatives and the other residents in Kauai, he realized that the Hawaii the world is familiar with is a fantasy; it obscures the colonial displacement, hyper-exploitation of workers, and destructive environmental extraction that have actually shaped life on the island for hundreds of years. At the heart of it all, “Cane Fire” aims to highlight the injustices local residents have endured for decades, and the need for them to be the ‘heroes’ on their own land.

Near the end of the film, the shot of Waimea Canyon—peaceful, untouched by corporate greed—gave me goosebumps. For this critic, that shot symbolizes Hawaii’s unwavering promise despite the centuries of exploitation; it is something equaled by the locals’ resolve and resilience despite the injustices that they face on their own land. That, in itself, is the true ‘Spirit of Aloha.’

“Cane Fire” opens in US theaters in May 20, 2022. Watch the trailer below.

“Cane Fire” opens in US theaters in May 20, 2022. Watch the trailer below.

Support the Site: Consider becoming a sponsor to unlock exclusive, member-only content and help support The Movie Buff!