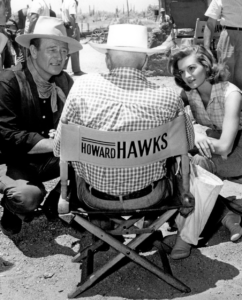

In December 2022, ‘Sight & Sound’ released its once-a-decade ‘Greatest Films of All Time’ ranking. This was the year the list blew up, with unprecedented changes throughout the entire Top 100, including at the top. With this essay series, we’re exploring the films that were new to the Top 100, and those that were bounced from the list. The goal is to analyze — and enjoy — each film, considering its current or former position in the canon, stepping back from the hot takes and manufactured controversies to evaluate a film on its merits. The first pairing in our series looked at a new entry, Charles Burnett’s “Killer of Sheep” (1977) and a recent deletion, Robert Altman’s “Nashville” (1975). In the latest essay, we wrote about another new addition, Barbara Loden’s debut Wanda (1970). Below, we consider a former member of the Top 100: Howard Hawks’ “Rio Bravo” (1959).

The eclectic auteur Howard Hawks (1896-1977) oversaw a dizzying variety of studio films throughout his career. With relative ease, Hawks meandered through genres, casting a subversive eye on the screwball comedy (“Bringing Up Baby”), musical (“Gentlemen Prefer Blondes”), even a religious epic (“Land of the Pharaohs”). For such a restless, ambitious director, it’s a letdown that Hawks exhibited an uncharacteristic degree of complacency with his Westerns. Hawks didn’t dare try to rewrite the textbook John Ford trademarked, and his “Rio Bravo” suffers from this lack of imagination. Ranking at 101nd in the latest ‘Sight & Sound’ Greatest Films poll marks a steep fall from its 2012 position (63rd), signaling less a shift in taste for Hawks than potential fatigue for an out-of-favor genre. Bereft of the bite and wit of early Hawks, this 145-minute morality play is too familiar to feel fresh, conventional fare from a beloved Hollywood hand.

Too Familiar to Feel Fresh

Plenty of Hawks-heads might reject that assessment, not just the thirty international film critics and four directors who included Rio Bravo on their Top 10 ballot for the ‘Sight & Sound’ list. French New Wave legend Jean-Luc Godard (he and his Cahiers du Cinéma colleagues revered Hawks) lauded it as “a work of extraordinary psychological insight and aesthetic perception.” Peter Bogdanovich, another critic-turned-boy-wonder-director — and preeminent Hawks scholar/fan boy — was particularly fond of “Rio Bravo’s” opening minutes, in which the plot is explained with all action and no dialogue. But, words aren’t necessary for such a straightforward, recycled conceit. Local lawmen John Chance (John Wayne) and Dude (Dean Martin) struggle to impose law and order on their small town, beset by the usual lineup of freedom infringers: outsiders, the lure of drink, and a beautiful woman.

What’s particularly disappointing about the token siren Feathers (Angie Dickinson) is that Hawks doesn’t know what to do with her, besides forcing her into the arms of Chance. It’s an odd fit, and an unfortunate arc, since the sparks between those two stars never flicker. In Hawks’ earlier gems, most of the men (Cary Grant in “Bringing Up Baby,” Gary Cooper in “Ball of Fire”) are overmatched by wily, whip-smart eccentrics (Katharine Hepburn, Barbara Stanwyck, respectively), but the chemistry is palpable and the build-up to their eventual coupling bumpy and rewarding. Chance’s eventual romance with Feathers, however, is an awkward, perfunctory partnership. It is exemplified by the final scene in which Chance basically announces ownership of Feathers, declaring she’s only allowed to dance for him. He then takes her underwear and throws it out the window.

Codes of Conduct, Friendship, and Masculinity

Much of the film is spent in the claustrophobic confines of a jail cell, overseen by Chance, Dude, and Stumpy (Walter Brennan, in his most Walter Brennan role). It’s a glorified locker room, with Chance playing the big brother/bully to the underachieving alcoholic Dude. And the functioning alcoholic Stumpy doesn’t disappoint anyone, because well, the bar is low. So low, in fact, that when he accidentally shoots at Dude, the pals just laugh it off. It’s a rare moment of levity, serving up believable, goofy humor that loosens up the tension, and shows some elusive humanity from the intimidator (Wayne) and his charges. Setting so many key scenes inside of small rooms evokes a chamber drama, far from a satisfying, sprawling wide-open Western. The genre’s unequivocal successes (“The Searchers,” “McCabe & Mrs. Miller,” “Meek’s Cutoff”) depicted the great outdoors as both enemy and ally, whereas here it’s a background character.

Examining codes of conduct, masculinity, and friendship was a career-long fixation for Hawks. Compared to earlier triumphs, however, “Rio Bravo” glides over characters’ emotions and eschews their inner lives. The film is more comfortable on the surface, redolent of the post-Hays Code Hollywood formula which ensured the bad guys lose and the good guys win, and the best guy gets the girl. Dickinson and Martin provide fleeting bursts of compassion which are consistently offset by the caricatures evoked by Brennan and Wayne. Reducing them to men who have jobs to do cheapens their complexity, and shrinks the film’s scope. That “Rio Bravo” has retained such a loyal following among the cinematic cognoscenti is a bit baffling, given modern audience’s perceived impatience with a simplistic, down-the-fairway tribute to professionalism and justice.

‘Rio Bravo’ Holds Up, a Testament to Hawks’ Craft

After the disastrous “Land of the Pharoahs” (1955), Hawks opted to run, not walk, to comfortable terrain, enjoying himself so much with “Rio Bravo” he would revisit the same theme in both the “El Dorado” (1966) and “Rio Lobo” (1970) remakes, also starring Wayne. The two had previously teamed up in “Red River” (1948), another by-the-book Western which gained reputation as a “stealth queer classic.” Finishing his career with replicas of “Rio Bravo” marked a curious turn for Hawks, a director famous for his daring fluidity. Still, “Rio Bravo” is a surprising stalwart, ranking ahead of all Hawks’ films and third among Westerns on ‘Sight & Sound’s’ list. Despite falling from the Top 100, it’s a Hawks-fest just beneath that cutoff: “Bringing Up Baby” (1938; tied at 108), “Only Angels Have Wings,” (1939; 122nd) and “His Girl Friday” (1939; 129th).

Voters may have had a hard time picking just one Hawks film, so “Rio Bravo” is likely victim and beneficiary of that inclination. Still, his early career — including the underrated, Billy Wilder-scripted “Ball of Fire” — is what I think about when I think about Hawks. These cackling, zany comedies — even “Only Angels” — have a distinct, madcap energy, pulsating with delicious camp and delirious imbalance “Rio Bravo” can’t match. The decline of the Western doesn’t explain “Rio Bravo’s” fall from canonical grace, but it’s not for nothing that only two Westerns remain in the Top 100: “Once Upon a Time in the West” (1968; tied at 95) and “The Searchers” (1956; 15th). It’s hard to see this trend reversing; but for Hawks to hold up is a testament to his craft, even if the greatest compliment for his most beloved Western is that it still counts as a Hawks film.

The next essay in this series will be out in November.