After the 1970s ‘New Hollywood,’ American cinema found its new voice in the ’90s with up-and-coming young filmmakers who took the scene by storm. Alongside Quentin Tarantino, the Coen brothers, Richard Linklater, and many more, there is one filmmaker who shocked the world with his dark, gritty, and powerful storytelling—David Fincher. In 1995, the world became shocked by his film “Se7en.” With that film, Fincher explores the dark psyche of human beings and the perversion of modern society as a whole, a theme prevalent in his later career. Although “Se7en” has its merits as it explores the darker alleys of the human psyche with an even more shocking conclusion, Fincher truly finds his voice in his next feature, “Fight Club.”

Based on the novel by Chuck Palahniuk, Fincher explores the themes of the perversion of society with the existential quest of finding meaning of life in a mechanized modern civilization and the destruction of meaning by sheer chaos. Again, he takes the path of psychological exploration of the characters, but this time in a more mature manner. Although the film is now considered a cult classic, the initial response to the film was not so good. Critics found it amoral and nihilistic, mostly due to its ending. But as time passes, it is the perfect moment to reevaluate the film. As an attempt to do that, in this article I seek to analyse the film by examining the characters through the lens of psychoanalysis. So, without further ado, let’s deep dive into the filmic text of “Fight Club.”

A Critique of a Mechanistic and Consumerist Society

“Fight Club” tells the story of an unnamed everyman (Edward Norton) who is fed up with his white-collared job and suffers from severe insomnia. To overcome this, he goes to support groups, posing as a sufferer of testicular cancer and other afflictions until another imposter named Marla Singer goes to the same support groups and disturbs his bliss. On a flight, he meets a cool and handsome man named Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt). One day, the narrator’s condo gets into fire and he shifts with Tyler into his dilapidated house. Soon they find out an emancipating experience in fistfights between them.

The experience, which only starts between them, soon becomes an experience for many dissatisfied persons with white-collar jobs or so. As a result, they create an underground fighting facility called the ‘Fight Club.’ But the situation complicates when Tyler begins a sexual relationship with Marla and forms a quasi-terrorist organization called ‘Project Mayhem’ to destroy all the corporate credit card companies to end their consumer dictatorship and emancipate humanity once and for all.

The film has an overtly critical view of modern consumerist society and how it creates a mechanized lifestyle. In the mechanized lifestyle, the meaning of becoming an individual is lost. In this situation, everyone lacks individual identity, and everyone’s identity can be interchangeable with others. This is a paradoxical condition that philosopher Marc Auge calls ‘supermodernity.’ Tyler’s aim is to restore individual identity and emancipate everyone from their mechanized lifestyle.

Freudian Mechanisms at Work

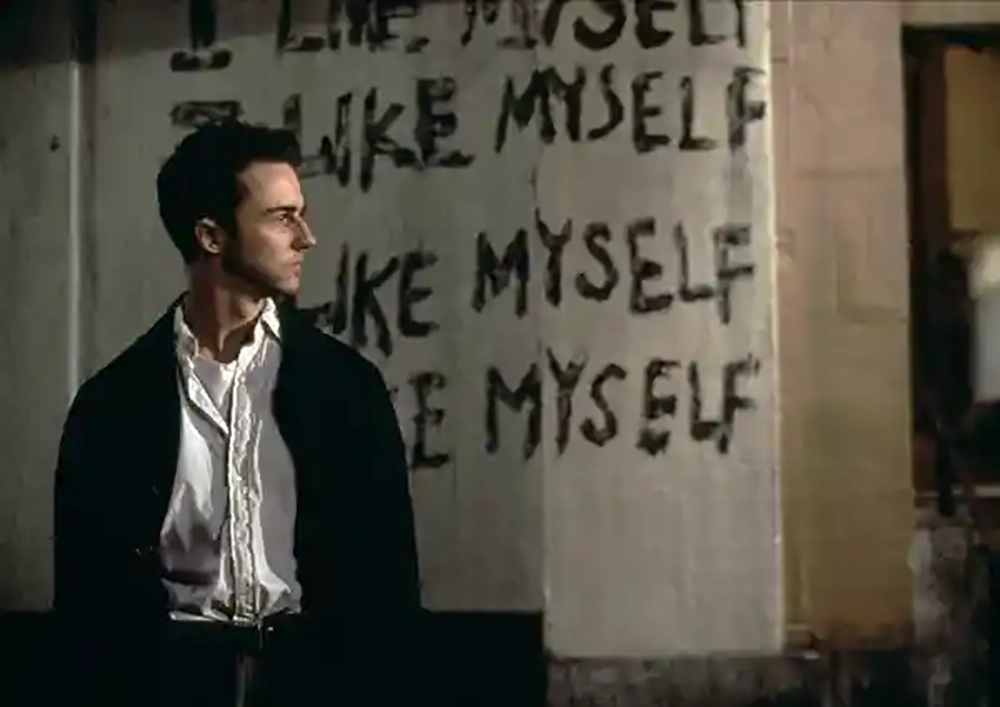

Therefore, his act of destruction of the credit card companies in the end is a symbolic act for that very means. He wants to show people that what they think they are is not their true self. They’re so engrossed in their consumerist lifestyle that they are bound to think in a certain way. And to end that, they have to first lose everything related to their consumerist lifestyle (the credit card companies symbolize that). “It is only after they lose everything that they are free to do anything,” according to Tyler. Most interestingly, this thought lies under the very fallacy of becoming true to self. Tyler is nothing but a projection of the narrator. He’s just someone the narrator aspires to be but can’t fully become. And with this dichotomy of what ‘you truly are’ and what ‘you think you truly are’ is the very crux of “Fight Club.”

The main protagonist of the film, the unnamed narrator, is an everyman who has a white-collar job in a major car company. In the mundanity of the work, he feels stuck and just drifting away. He is also an insomniac, worsening the matter even more. At this very delicate moment of his life, he unknowingly creates his alter ego, Tyler Durden. Tyler has everything our narrator aspires to have. According to Tyler himself, “You are looking for a way to change your life. But you could not do this on your own. All the ways you wish you could be… that’s me.”

The narrator is the archetype of a lost soul in a modern mechanized society. He just wants to become someone who is free in all ways. And that is Tyler. He is emancipated from all the bounds of society, and thus, he is free to do anything. So, the narrator chooses Tyler, but as the film progresses towards the end, he comes to face the evil plans of the destruction of the very fabric of mechanized existence. But by doing so, he is not emancipating humanity from their mechanized existence driven by the consumer dictatorship. Rather, he creates his own mechanization of existence by preaching his anti-consumerist ideals to the people who feel trapped. Thus, the narrator and Tyler symbolize two end points of personalities in a spectrum.

Freud’s Id, Ego, and Superego

In Freudian terms, personalities are largely shaped by the enduring conflict between aggressive urges and the inner social control over them. Freud theorizes that our mind is divided into three interacting parts: id, ego, and superego. These parts provide a better ground for this conflict to shape the personalities in a person. If we take the classic Freudian iceberg into consideration, we can identify that the large hidden, buried underwater chunk of ice as the unconscious mind. The id represents this hidden part of our subconscious mind. The id controls all the immediate and aggressive urges of a mind like food and sex. And it has its exact opposite in the upper portion of the iceberg as the conscious mind. The superego represents this conscious mind and it controls all the pragmatic urges of a human mind.

In the context of “Fight Club,” Tyler Durden signifies the unconscious, aggressive urges of the unnamed narrator. So, he represents the id; and on the flip side, the narrator represents the superego having a pragmatic and realistic view of life. But as the id and superego never get along with each other, so, the narrator has to oppose Tyler’s plan of destruction. But this creates a paradox as the narrator finds a new life after meeting (creating) Tyler. Before that, he was too engrossed in his consumerist and materialistic lifestyle. He thinks to live a good lifestyle with a cozy sofa and some good furniture—or make his life more lavish with furniture—is the point of life.

‘Fight Club’s’ Ambiguity its Most Fascinating Takeaway

However, the point Fincher is trying to make is this does not elevate his living. The things he owns end up owning him. So, by creating Tyler, he finds an alternative. But Tyler also tries to own him (the narrator). Thus, through the lens of psychoanalysis, the film suggests the gripping study of order and chaos. One always tries to overpower another in this tussle. But if one overtakes another, it will annihilate the very fabric of existence.

Among many issues, dealing with human psychology is the most fascinating aspect of “Fight Club.” The dark subjectivity makes the film very ambiguous, just like our subconscious’s uncertainty. Many people feel it is just a story of violence, sex, masculinity, and nihilism—but it is beyond that. It tells us about our psychological conditions in just the mainstream way.