Curiosity is considered the real mother of invention–the mother of all knowledge. Everything is driven by that intrigue of exploring the unknown or what we don’t understand and would like to grasp. American experimental director Jem Cohen uses “the mother of invention” as the crux of his filmmaking process, delving into what he deems extraordinary and mysterious to create observational pictures about an array of topics, whether it is documenting the development and growth of the post-hardcore band Fugazi in “Instrument” (1999) or painting a portrait of the New York City urban landscape in “Lost Book Found” (1996). It oozes from his frames. The lens captures the spirit of inquiry from the man behind the camera and the subjects’ creativity.

Jem Cohen’s Aim for the Curious-Minded

This peculiar filmmaking approach highly deviates from the mainstream documentary mold. It is one of the reasons why many consider Cohen a “punk” figure in the arthouse scene. He rebels against the norm. Cohen forms fascinating projects that are way different than what is usually shown in most theater chains and streaming platforms. Anti-corporate and solely by himself, Cohen is a figure that must be admired and respected by cinephiles worldwide. He makes films for curious people only. However, Cohen wants to amplify the mind and make the viewer more interested and fascinated by the unknown instead of sticking to their regular conformities. He does not refer to cinema and the arts but science as well, as we see in his latest piece of work, “Little, Big, and Far” (having its world premiere in the Currents section of this year’s New York Film Festival).

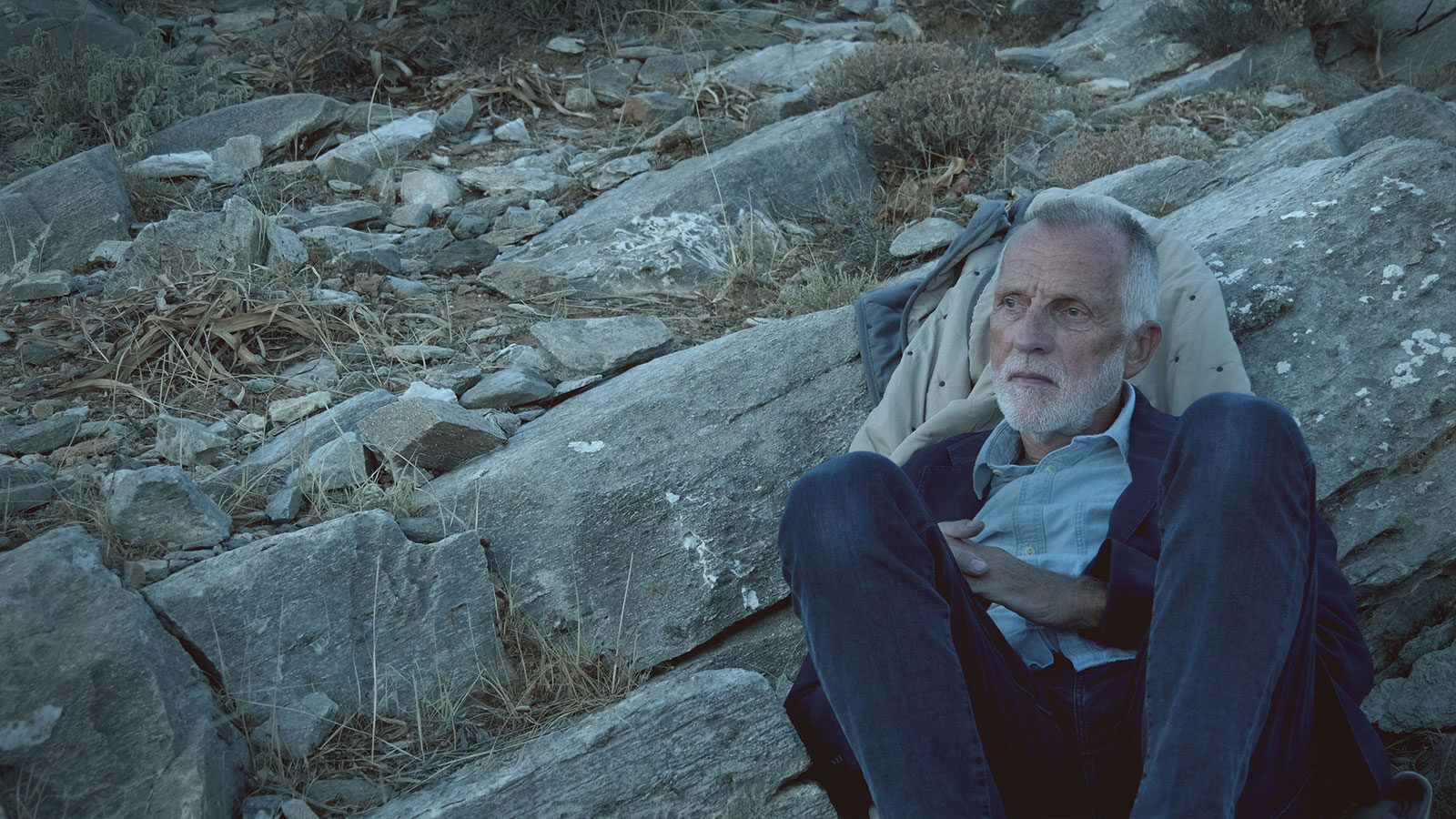

The feature is similar to his previous works regarding adventurous and curiosity-driven approaches. But something in its crux makes it feel more expansive than what he has done before. He intertwines modern-day isolation and despondency with the broad universe amidst the stars. Both are hard to understand and grasp with ease. Yet, you can explore them. Jem Cohen shows this division through Karl’s eyes. Having just turned seventy years old, Karl is an Austrian astronomer who looks back at his life professionally and personally. Karl feels that this is the best moment for him to reevaluate everything he has done with the dying field of astronomy and the experiences with his wife, Eleanor (experimental director Leslie Thorton, who, like Cohen, is also making films to make sense of the vast, strange world).

They never see each other in person throughout “Little, Big, and Far.” The two communicate by reading telegrams aloud. Karl and Eleanor converse about their careers and life decisions, which are interconnected with their galaxy studies. The mystery of what lies beyond mixes with our doubts about human connections and how they develop as we age. That is one of the many interconnections that Cohen makes during the film. Conversations about love, life, and death intersect with footage of the stars and the world beyond our eyes to reflect on the many unsaid and unanswered, both in science and our personal lives in or out of romantic relationships. Karl also communicates with a graduate student greatly interested in his work and approach to astronomy.

A Collision Course of Experimental Minds Coming Together

She often glances at some of his findings and the now-demolished Arecibo telescope, which I love as a Puerto Rican myself. The student compares the dismantling of the renowned telescope to the removal of someone special in your life. It makes sense that she thinks that way since her path in the film involves her connecting with another student, younger than her, with whom she had a date with not so long ago. The two go through records and documents about the previously mentioned topics as they go through a rekindling of emotional fire. That is like exploring the unknown that captivates Cohen and Karl. Two stars colliding… what will make of it? That is for the two young searchers to discover.

Meanwhile, Karl plans to visit Greece to see a wonder he has never encountered. He might never have the chance to do so if not now. It is a beautiful sight like no other. That demonstrates the vast universe he has been curious for decades to explore. And in the latter stages of “Little, Big, and Far,” we get to glance at it for about eight minutes alongside Karl. It is astonishing and breathtaking scenery. You see a limitless sky full of stars, containing the world’s past, present, and future in one view. Cohen stays with this image for an extended period, not because it is beautiful, albeit one could stare at it for hours. But because it captures what he wants to say about the film and his filmmaking aim.

It reflects the past, in which Karl looks back at his life work and personal notes. Above all, there is the pondering of the future. The two young astronomers venture into a dying field and a world slowly losing the intimacy of human connection. Our worries about space cross with our existential crisis in a post-pandemic world. Cohen again shapes and molds his filmmaking vision to combine many elements with intrigue for what surrounds us. Fiction and documentary, the personal and professional, all come together in a collision course of experimental minds. A segment of the film that best describes “Little, Big, and Far” is right at the beginning, where Karl compares space with jazz, as he plays a record by John and Alice Coltrane, “Cosmic Music” from 1968. Sure, the album’s name hints at his comparison, as it alludes to his profession.

Karl sees how the uniformity and the diverse ways of expression in jazz music replicate in astronomy and space exploration. Contrane’s instrumentation is freeform. She orchestrates in a way that relocates the rhythm and pattern of her records. This is much like the broad galaxy light years away. It is abstract, similar to Cohen in the director’s chair. “Little, Big, and Far” is constructed from that lucid comparison. The project provokes plenty of thought. It expresses some of our hidden emotions through a canvas we don’t recognize yet are curious to explore. There aren’t many films like this or directors akin to Cohen’s tenure in curating unique, wayward experiences. And he hasn’t been close to losing his “punk” posture, even when delving into the personal on his latest piece.

“Little, Big, and Far” had its world premiere in the Currents section of this year’s New York Film Festival, which ended on October 14th. Follow us for wrap-up coverage.