As my coverage of this year’s Santa Barbara International Film Festival drew to a close, I set my sights on three distinctly different documentaries: Tadashi Nakamura‘s “Third Act,” Nova Ami and Velcrow Ripper’s “Incandescence,” and Howard Berry‘s “Her Name Was Moviola.” Nevertheless, I realized afterwards how connected those documentaries are. Their narratives focus deeply on preserving something valuable—whether it’s the analog techniques of filmmaking, the cultural and familial history of an Asian American family, or the ecological wisdom of Indigenous fire management.

All three films grapple with legacy—what we preserve, what we discard, and who gets to decide. “Third Act” and “Her Name Was Moviola” are love letters to fading worlds (analog film, the immigrant father as myth). On the other hand, “Incandescence” argues that some legacies, like fire, can’t be contained. Together, they ask: How do we honor the past without becoming its prisoner? Each documentary highlights the importance of honoring and safeguarding knowledge, traditions, and practices that risk being lost. And while ultimately these films aren’t flawless, they’re nonetheless alive—messy, urgent, and unafraid to get their hands dirty. And for what it’s worth, isn’t that what cinema is for?

Here are a few thoughts on “Third Act,” “Incandescence,” and “Her Name Was Moviola.”

‘Third Act’: A Father, a Son, and the Frames Between

“My whole life I always knew I had to make a film about my dad.” Tadashi Nakamura’s opening line isn’t just a mission statement—it’s a confession. The camera zooms in on grainy childhood photos of the Nakamura family: a toddler Tadashi in a UCLA onesie, his father Robert in a director’s chair, and a clapperboard marked “Prince” (Tadashi’s son) that bridges generations. We hear Tadashi’s childhood voice, tinny and earnest, interviewing his father: “What’s the secret of success?”

Young Robert, ever the professor, replies: “You’ve gotta have a vision.”

But “Third Act” isn’t a victory lap. When Robert, the godfather of Asian American cinema, is diagnosed with Parkinson’s, Tadashi’s film shifts from chronicling his father’s legacy to confronting mortality. Robert’s career is staggering—he co-founded Visual Communications (the first Asian American media collective), directed the groundbreaking “Hito Hata: Raise the Banner” (the first feature film by and about Asian Americans), and mentored a generation of filmmakers. Yet Tad digs deeper, unearthing his father’s internment at Manzanar, his battles with depression, and the generational chasm between Robert’s stoic upbringing and Tad’s own search for identity.

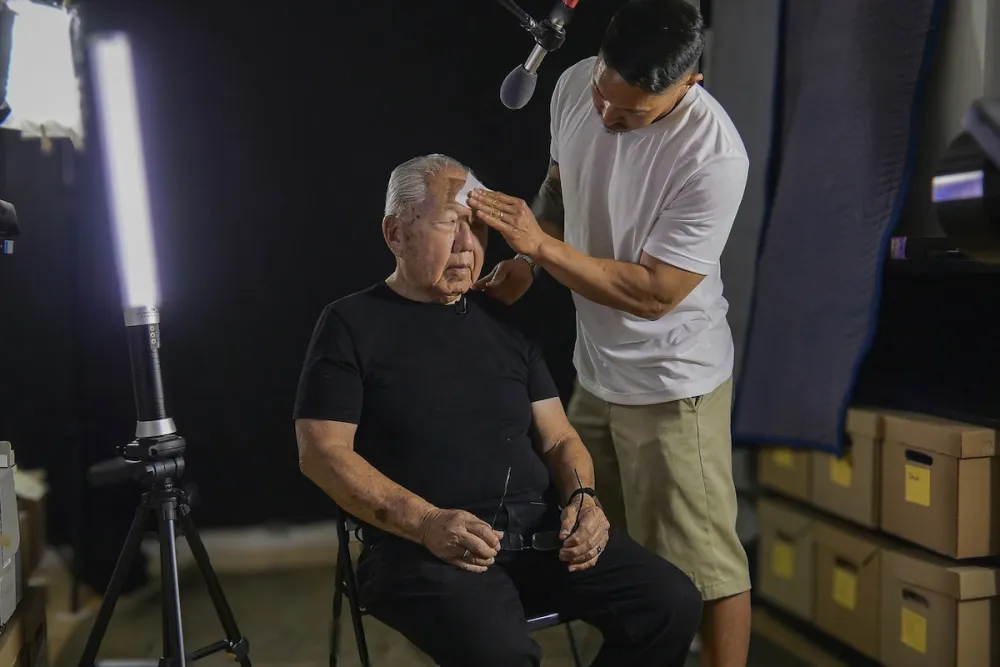

The documentary layers archival footage of Robert’s early work—like his 1974 film “Wataridori: Birds of Passage,” which documented Tadashi’s grandfather—with present-day scenes of Robert grappling with his fading health. A particularly raw moment shows Tad screening a rough cut of “Third Act” to his father. Robert, now frail and slurring his words, critiques the pacing: “Too slow…needs music here.” Tad’s face tightens; it’s a collision of filial duty and artistic pride.

An Intimate Documentary on Legacy and Intergenerational Storytelling

The film’s title comes from a question Tadashi asks his aging father: “What’s your third act?” Robert, ever the pragmatist, deflects with a joke. The answer, of course, is this film—a final collaboration that spans seven years, capturing Robert’s decline and Tadashi’s evolution as a father himself.

Among the many strengths of this documentary is its honesty. Here, Nakamura avoids hagiography. When Tadashi’s son Prince asks about Manzanar, Robert’s silence speaks louder than any lecture. In another scene, Tad unearths old letters revealing his father’s suicidal ideation during the 1980s—a revelation that fractures the myth of the “godfather” and rebuilds him as a man. The film occasionally leans on formula (archival montages, talking-head academics), but its power lies in the unsaid. When Tadashi films Robert’s trembling hands arranging family photos, the act feels less like documentation than communion.

“Third Act” isn’t just a film about a father and son; it’s about the stories we inherit, the ones we rewrite—and the ones that slip through our fingers.

Grade: B+

‘Incandescence’: When Fire is a Cure, and Not the Curse

“What will the world be without fire?” That question lingers like smoke over Nova Ami and Velcrow Ripper’s “Incandescence,” a documentary that reframes wildfires not as apocalyptic spectacles but as ancient, necessary rhythms. With its showing coinciding with the catastrophic January 2025 Southern California wildfires—which torched 1.2 million acres, displaced 200,000 residents, and turned Malibu into a charred moonscape—the film feels less like a warning than a eulogy.

What I find refreshing with the documentary is how the directors avoid the usual disaster-porn visuals. Instead, they train their cameras on the fire’s aftermath: beetles carving patterns into charcoal, ospreys nesting in skeletal trees, and Indigenous firefighters reigniting controlled burns. A Karuk elder explains how her ancestors used “good fire” to cleanse the land, a practice outlawed by colonizers. The irony stings: modern fire suppression, designed to “protect” forests, created tinderboxes. Now, as megafires rage, we’re scrambling to relearn what Indigenous communities never forgot.

However, “Incandescence” isn’t content to dwell on the past. The film pivots to the present, where communities are redefining resilience. We see a retired firefighter turned permaculturist who’s transforming his scorched property into a fire-adapted homestead. He plants fire-resistant native shrubs, creates defensible zones, and even builds a “fire garden” to educate neighbors. “Fire isn’t the enemy,” he says, raking dried brush.

“Ignorance is.”

An Incisive Exploration of Fire’s Duality of Destruction and Rebirth

Personally, I feel that the film’s boldest choice is its soundscape. There’s no score—just the crackle of flames, the hiss of embers, and the eerie quiet of a forest floor post-fire. It’s immersive, almost uncomfortably so. When a survivor describes fleeing her home, her voice merges with the roar of a blaze until you can’t tell where the memory ends and the present begins. We also follow firefighters battling the infernos, their faces streaked with soot and exhaustion. At the end of the day, these aren’t heroes in capes—they’re ordinary people navigating a world on fire.

But here’s the rub: “Incandescence” isn’t really about fire. It’s about hubris. We see drones mapping burn zones, politicians spouting empty rhetoric, and a tech bro peddling AI-powered fire predictions. None of it masks the truth—that we’re guests in a world that doesn’t need us. The film’s most haunting image isn’t a burning house but a single sprout piercing ash. It’s a reminder that Earth endures, with or without our permission.

What lingers isn’t despair, though; it’s defiance. The final act shows a prescribed burn on the mountains, where Indigenous rangers and white landowners collaborate to clear underbrush. Flames creep, not rage, across the landscape. It’s a searing acknowledgement, one that Ami and Ripper manage to convey: fire is a partner, not predator. As a call to action, “Incandescence” yearns to light a path forward: to survive this era of flames, we must stop fighting fire and start learning its language.

Grade: B-

‘Her Name Was Moviola’: Love, Grease, and the Analog Ghosts of Cinema

Let’s get this out of the way: “Her Name Was Moviola” is a film nerd’s paradise. It’s also a eulogy for a machine that revolutionized cinema—and a middle finger to the digital age.

The Moviola, invented in 1924, was the first machine that let editors physically cut and splice film. It’s clunky, loud, and smells like grease (according to Walter Murch, who should know—he edited “Apocalypse Now” on one). Director Howard Berry and Murch embark on a quixotic mission: take a scene from Mike Leigh’s “Mr. Turner,” convert it back to 35mm, and edit it the old-fashioned way.

The process is absurdly laborious. We watch Murch squint at film strips, hand-label reels, and wrestle with a machine that looks like a cross between a sewing machine and a tank. At one point, he jokes that editors used to get “film rash” from handling nitrate.

The Tactile Grit of Analog Tools—and How Modernity Renders Them Obsolete

But here’s the thing: the Moviola mattered. Before digital editing democratized filmmaking, the machine was a gatekeeper. Only those with the patience (and calluses) to master its quirks could shape stories. Berry doesn’t romanticize the past—he shows the Moviola’s flaws, like its tendency to chew up film—but he makes a sly case for analog’s virtues. Digital editing is faster, sure, but where’s the tactile joy of threading film through a machine? Where’s the camaraderie of editors huddled over a Steenbeck?

The film’s climax is a screening for Leigh, who grumbles about Murch’s edits. It’s a delicious moment: two legends debating cuts like it’s 1975. “Her Name Was Moviola” isn’t perfect—it drags in technical deep dives—but its heart is in the right place. In an era where films are “processed” more than crafted, Berry and Murch remind us that art isn’t just about the final product.

Sometimes, it’s about the grease under your nails.

Grade: B

“Third Act,” “Incandescence,” and “Her Name Was Moviola” screened at this year’s Santa Barbara International Film Festival. The festival ran from February 4 to 15, 2025. Follow us for more coverage.